The hurricane seasons have been so intense lately that it’s hard to keep abreast of the fallout. Earlier this month, the Washington Post took us to Ocracoke, a North Carolina barrier island in the Outer Banks that’s seriously debating the question of whether to rebuild or retreat.

This debate will come as no surprise to residents of most coasts, on some of which the question of whether to stay home and defend battered homes and traditions among rising shores, risk, and insurance costs has become the stuff of persistent nightmares.

The rest of us, in the meantime, are liable to lapse into a denial that’s even bigger than climate change denial. But that won’t last — especially as the Russian Roulette of hurricane season brings frantic media attention to one beloved coastal landmark after another.

Scientists have long warned that Ocracoke’s days are numbered, that this treasured island is a bellwether for vast stretches of the U.S. coast. “Virtually everyone from Virginia Beach south to the U.S./Mexico border is going to be in the same situation in the next 50 years,” said Michael Orbach, professor emeritus of marine affairs at Duke University. “And it’s only going to get worse after that.”

Interesting Policy Problems, Even More Interesting Human Stories

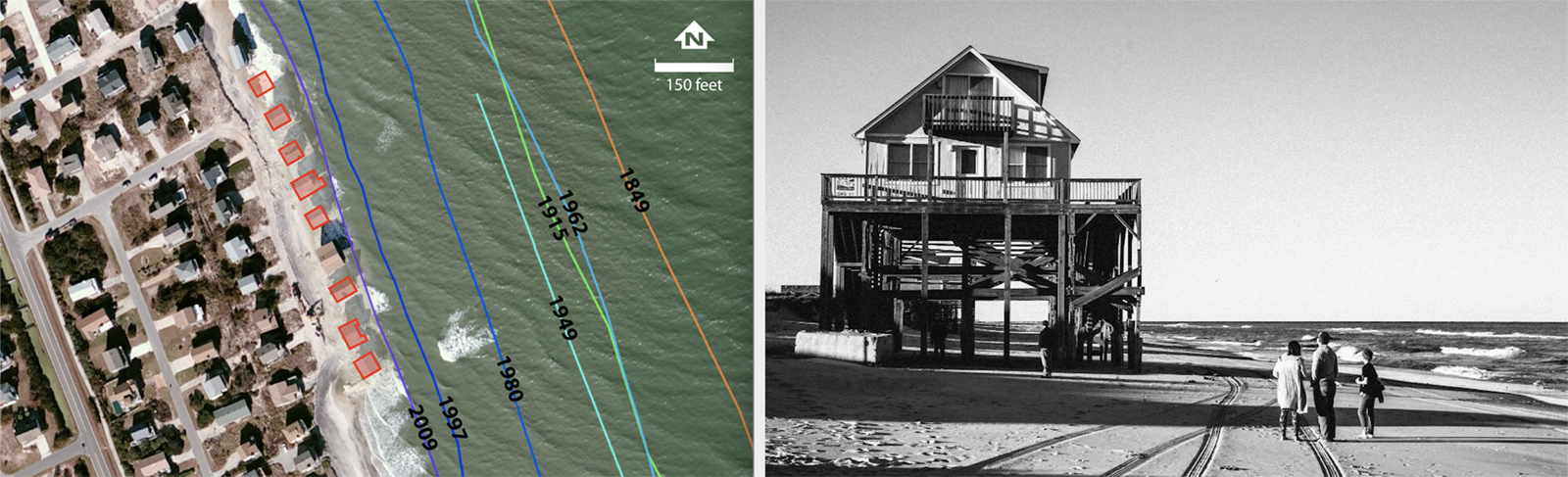

While some residents and businesses in Ocracoke begin to rebuild, maybe on higher stilts or with better weather sealing, a tale of coastal slower encroachment is told in Nags Head, further north, where some parts of the Outer Banks shoreline are disappearing as quickly as six feet per year. There, the erosion has created a slow-motion policy teeter-totter as the city implements policy for for safety and beach access and “nourishes” the shoreline by pumping sand from the sea floor onto the beaches — an engineering band-aid that costs tens of millions of dollars and lasts as little as two years. (“We’re not supposed to be here,” acknowledged John Ratzenberger, the town commissioner in charge of the project.)

What do you do if you’re a town that’s responsible to maintain public beach access while ensuring safety and services for the residents of East Seagull Drive, whose homes are in the path of an advancing Atlantic Ocean? You buy the houses and demolish them before the sea can do it — or you try.

It seems simple enough, but every single civic, county, or state action to impose a new logical human presence against the powerful advance of nature is going to come into conflict with colorful local characters, traditions, and history, as welk as a property-rights battleground unique to that place. It makes for a good read.

Even if the national spotlight doesn’t endure long after a hurricane or other major weather event, these stories are accumulating into a new literature in coastal America — and everywhere else where there’s a coast. It’ll make for good stories, but it also needs to build into logical practices and policies for climate retreat as the seas continue to rise.

0 Comments