EVs are the stuff of myths. So many myths:

- They’re too expensive! (Nope.)

- Their batteries hemorrhage range as soon as you drive them off the lot! (Noooooope.)

- Worthless in cold weather! (Nope! And Norway!)

- They’re less green than normal cars! (NOPE.)

Let’s put that last old argument out to pasture once and for all.

Skeptics have long called EVs eco-wolves-in-sheep’s-clothing. Their claims, namely that (a) batteries are made from un-green materials that must be extracted from the earth; and (b) EVs are fueled by the un-green grid, are rooted in truth, but don’t stand up to the big picture.

In the olden days, you could painstakingly win the argument by pointing out the electric engine’s vastly superior efficiency, and the constant greening of the grid in all U.S. states, and the perpetual improvements in batteries and their disposal and re-use. But the argument took time; you couldn’t quite bust the myth with a single, easy, argument-killing graphic.

BEHOLD, today, that elusive singe easy argument-killing graphic! Compliments of the Union of Concerned Scientists.

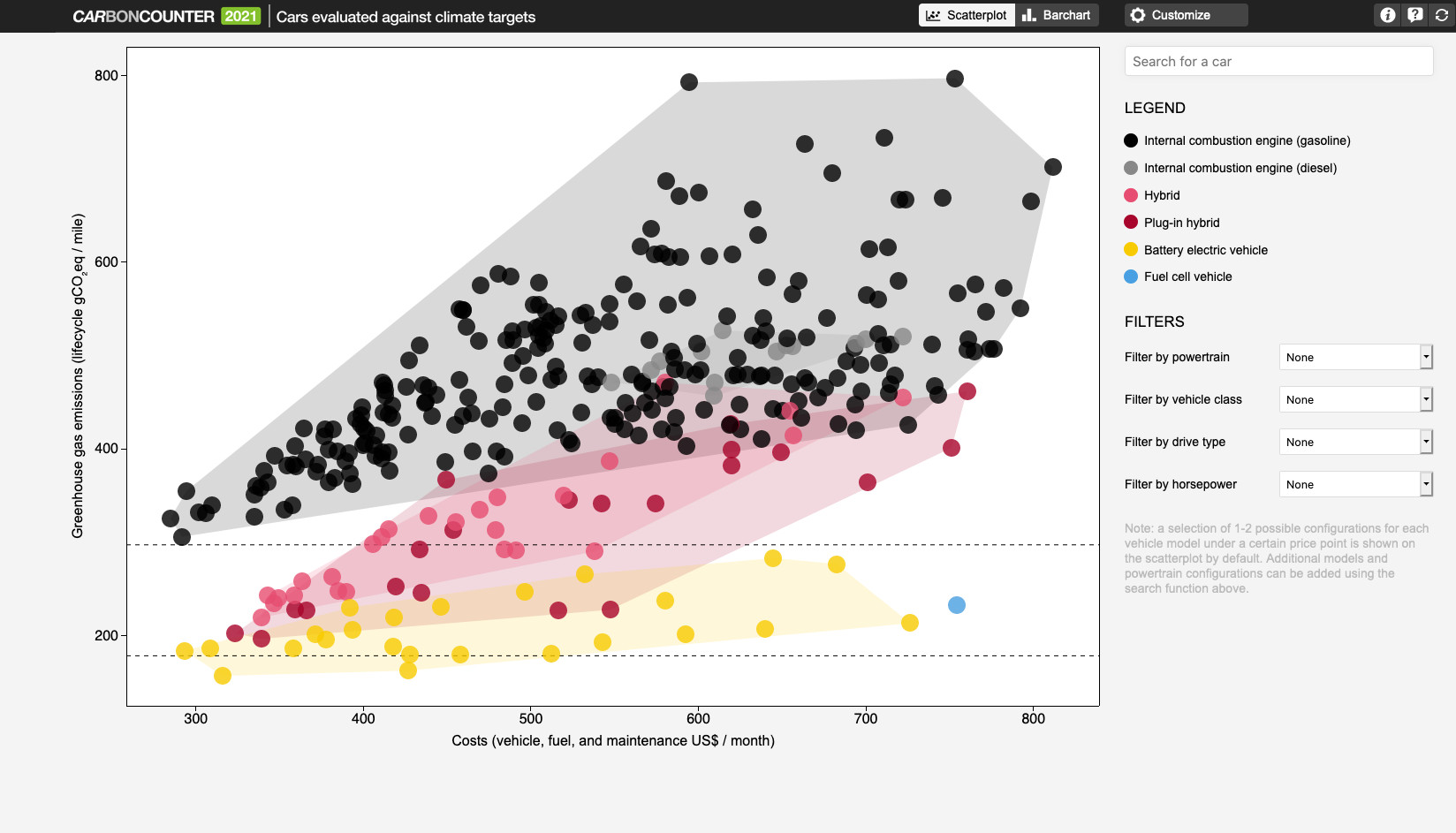

In said graphic, models of cars are represented by dots, with the black dots being conventional cars and the yellow dots EVs, plotted as emissions per cost. (The red dots are hybrid-eletrics, which are a transitional technology that’s being replaced as quickly as it’s been emerging.)

The Union of Concerned Scientists’ data have been shifting over time as all kinds of cars have improved, with EVs pulling away toward victory. This graphic illustrates the green-nesses of EVs and ICEs not only not intersecting, but not even coming close to intersecting. Not a single available internal-combustion model — no matter how expensive it is — is as healthy for the climate as any available pure electric model now being produced.

So, did the concerned scientists cherry-pick their data? Do they leave out the carbon cost of building the car and its batteries or disposing the car and its batteries? Nope — the “well-to-wheel” data take into account each vehicle’s full lifetime footprint from creation to operation to disposal.

Clear as the data are, they won’t end the myths. As William Totds wrote last year in the Guardian:

There will always be a new study with some flawed assumptions to keep us all busy and we could rebut these until we all drop. The advantage for the oil and diesel industry is that articles and reports, however poor, keep the controversy alive. Discrediting or distorting science is a political strategy, as Naomi Oreskes chronicles so well in Merchants of Doubt.

True enough. But in the real world the argument is over.

The intrepid English inventor Thomas Parker shows off his 1883 electric vehicle, fully 25 years before the first Model A rolled off Ford’s factory line and settled the electric vs. fossils question… for the time being.

Buy a Car Like It’s 2036

Consumer Reports reports that today’s cars will last an average of eleven years — and, with love, fifteen. So the ethical calculus has to factor the commitment of the earth to fueling the car you buy not just now, but also until 2036 or even later.

That’s right, your new Camry or Camaro still could be pulling up to the gas pump four presidential terms from now — by which time we may have shifted the grid entirely to renewables. With solar and wind continuing to wildly outpace fossil fuel development, by then we may not be drilling for oil for any purpose other than specialty plastics… and to keep obsolete cars alive.

The electric-vs-fossils decision is nothing new. Electric cars were being developed right alongside internal combustion vehicles across the early history of horseless carriagery. In the end, it wasn’t ethics that made the fuel decision for us, but the discovery of plentiful oil.

But today, the decision is very ethical and it’s a clear one.

Buying an electric car is the demonstrably “greener” personal decision. But larger than that, it sends a message to the auto industry that consumers are moving forward. It sends a message to government at all levels that it is time to invest in infrastructure around EVs, and start dismantling the massive, subsidized global machine we’ve built around petroleum.

And finally, perhaps, buying an EV is a “gateway” decision, which gets each of us individually thinking about how we can continue to green up our lives. If we have an EV, can we go a step further and build it a solar carport? Can we go a step further from there, and streamline things so the solar carport serves all our power needs?

Don’t get us wrong. Buying new stuff won’t save the world. But good decisions, in a larger sense, will. Something as impactful as the engine in your car needs to be a good decision.

0 Comments