I Am in Love with Kelp

“I am in love with kelp.” Let Tiffany Stephens’ words resonate through your Saturday… and calm your climate anxiety. This video from Noema might show the way toward a new climate creativity around kelp, an abundant form of plant life you might not think much about when you’re not strolling a rocky beach.

Love affairs with kelp aren’t exclusive to cold northern climates. Down here in Santa Monica Bay — as far away from Seagrove Kelp Farm in Doyle Bay, in some ways, sadly, as you can be — there are also those who love kelp. I should know — I am one of them!

Locally, down here in the Santa Monica Bay, our Kelp Forest Restoration Project is a deceptively simple project that has for years been working to shift the subsurface balance of power from purple sea urchins — which humanity has been empowering since 19th-century trappers and furriers exterminated southern California’s sea otters — back to the kelp which is the very basis of the underwater ecosystem. It’s an extraordinarily labor-intensive process, but it’s a labor of love for the divers who often balance hectic urban lives with this rewarding application of their love of the water.

Having worked on a predecessor of that project a decade ago, I never look at Santa Monica’s quiet, sublime sunsets without also seeing-feeling the kelp forests beneath the surface. Once sensitized, you can see-feel the kelp forests swaying and breathing down there, involved as they are in an existential struggle for a system of life that mirrors that of the forests on land. They’re also an elegant, and fluid analog of their beauty.

Pictures of sunsets, but also of kelp, and of people not necessarily knowing they’re also seeing-feeling kelp.

As someone who’s also lived and worked in and loved Alaska, it’s easy to cringe at the proposed introduction of another extractive industry there. It’s easy for all of us with chronic existential extraction fatigue to reflexively despise any new industry encroaching anywhere, on anything, not least of all on the earth’s wildest and most untrampled lands.

But… kelp is amazing. And, referring back to the above video, it’s hard not to be seduced by the marginal impact of those boats gently farming cultivated kelp (which will be further reduced through this decade as electric boat engines proliferate).

“This is an optimistic space for me because I see it as a replacement, as a substitute, for things that are more destructive,” says Stephens, and she lists just a few ways kelp can help reduce the impact of human life on earth. These aren’t just, as we might imagine, boutique things like sushi or cosmetics, but also workaday products like plastic replacements or concrete polymers.

Could a kelp industry, scaled to meet its potential, have less of an impact than oil extraction, for instance, or other industries whose lobbyists work so hard to protect them from those who would balance human appetites against preservation of the water and land?

Zero-impact industries are the creativity we need to see.

We admittedly don’t know any active truck drivers, but it seems like some of them might willingly trade this sunset for one from a dive boat, after a satisfying day restoring kelp beds, and with a promise of an evening at a seaside bar. All things considered, we would too.

Finally, as robots take the wheel from the hundreds of thousands of truck drivers and cab drivers who are only the next in line to lose their jobs and ways of life, the next collective creativity we need to deploy is how to shift all the potential energy of surplus human labor to things like kelp bed restoration or kelp farming.

Market forces might bring the kelp to market, just as they brought trees to market. But since market forces demonstrably do not result in stronger forests of any kind, what forces can we use to connect labor to the larger existential, climate-surrounded goal, which is nothing less than forests that are as strong as they were before we started using them as our pantry, on the one hand, and began killing the otters on the other.

Those forces are the new creativity we need to see.

An easy first step to help take us there: get in love with kelp.

Get Creative!

Watching the COP26 global climate talks from a rooftop 5,115 miles away, one thing is clear: it’s time to do the work. There’s no more time for doubters or denial on the one hand, or indecision or political traffic jams on the other.

At this point, the climate action stage should be filled with creativity. The seeds for this are planted. We’ve spoken to rooftop windmill makers, battery repurposers, solar-panel reconfigurers, no-BS climate communicators, serial forest nurturers, visionary climate adapters… and we know we’ve only scratched the surface.

Like all these neighboring rooftops, the climate challenge is a blank canvas. For most people we know, the question still remains, “but… what can I do?”

The answer is get creative. Whether it’s with an empty rooftop, or a pen, or a purchase, or a sewing machine, or a computer, or a vote, get creative.

Creativity is humanity’s superpower. And fellow superheroes, we have a world to save.

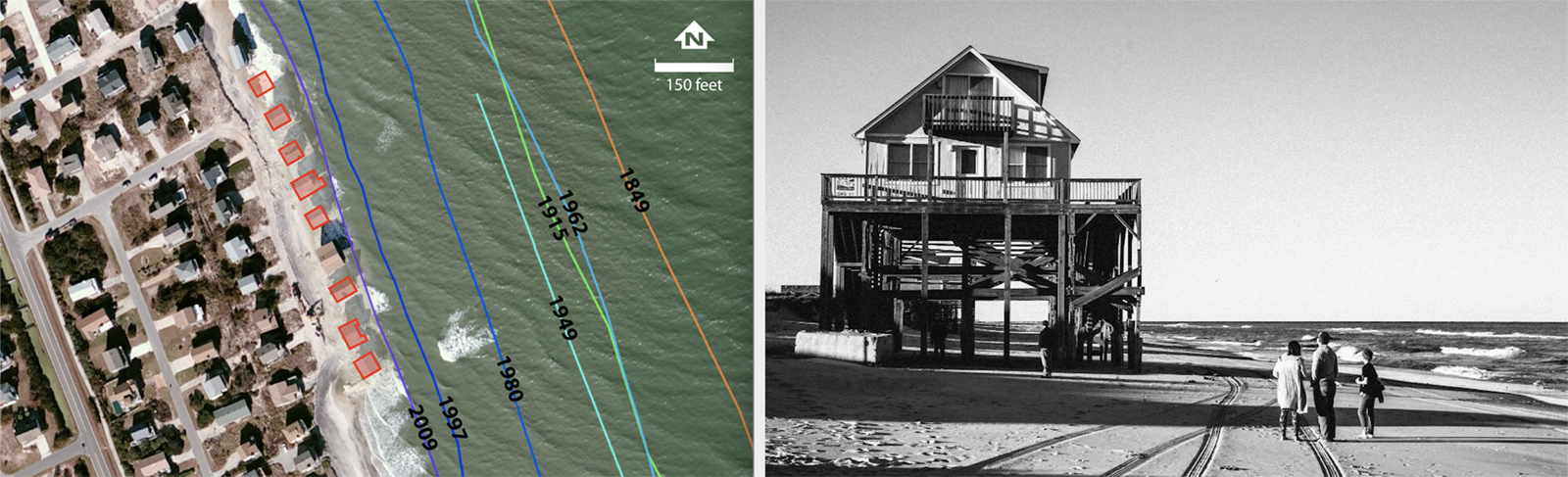

Rebuild or Relocate: Haulover, Nicaragua

The Gasoline Engine Is Officially Unethical

EVs are the stuff of myths. So many myths:

- They’re too expensive! (Nope.)

- Their batteries hemorrhage range as soon as you drive them off the lot! (Noooooope.)

- Worthless in cold weather! (Nope! And Norway!)

- They’re less green than normal cars! (NOPE.)

Let’s put that last old argument out to pasture once and for all.

Skeptics have long called EVs eco-wolves-in-sheep’s-clothing. Their claims, namely that (a) batteries are made from un-green materials that must be extracted from the earth; and (b) EVs are fueled by the un-green grid, are rooted in truth, but don’t stand up to the big picture.

In the olden days, you could painstakingly win the argument by pointing out the electric engine’s vastly superior efficiency, and the constant greening of the grid in all U.S. states, and the perpetual improvements in batteries and their disposal and re-use. But the argument took time; you couldn’t quite bust the myth with a single, easy, argument-killing graphic.

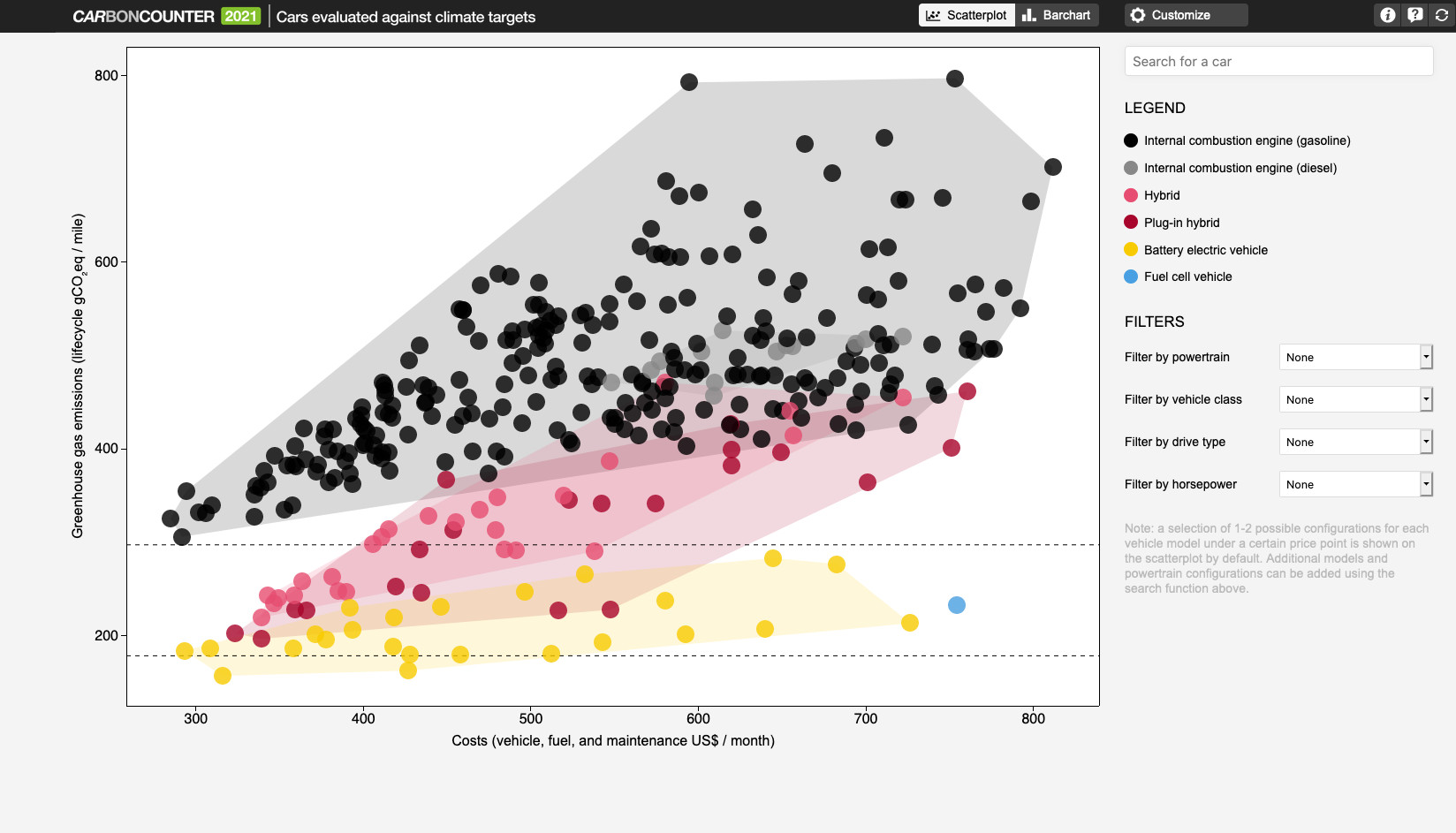

BEHOLD, today, that elusive singe easy argument-killing graphic! Compliments of the Union of Concerned Scientists.

In said graphic, models of cars are represented by dots, with the black dots being conventional cars and the yellow dots EVs, plotted as emissions per cost. (The red dots are hybrid-eletrics, which are a transitional technology that’s being replaced as quickly as it’s been emerging.)

The Union of Concerned Scientists’ data have been shifting over time as all kinds of cars have improved, with EVs pulling away toward victory. This graphic illustrates the green-nesses of EVs and ICEs not only not intersecting, but not even coming close to intersecting. Not a single available internal-combustion model — no matter how expensive it is — is as healthy for the climate as any available pure electric model now being produced.

So, did the concerned scientists cherry-pick their data? Do they leave out the carbon cost of building the car and its batteries or disposing the car and its batteries? Nope — the “well-to-wheel” data take into account each vehicle’s full lifetime footprint from creation to operation to disposal.

Clear as the data are, they won’t end the myths. As William Totds wrote last year in the Guardian:

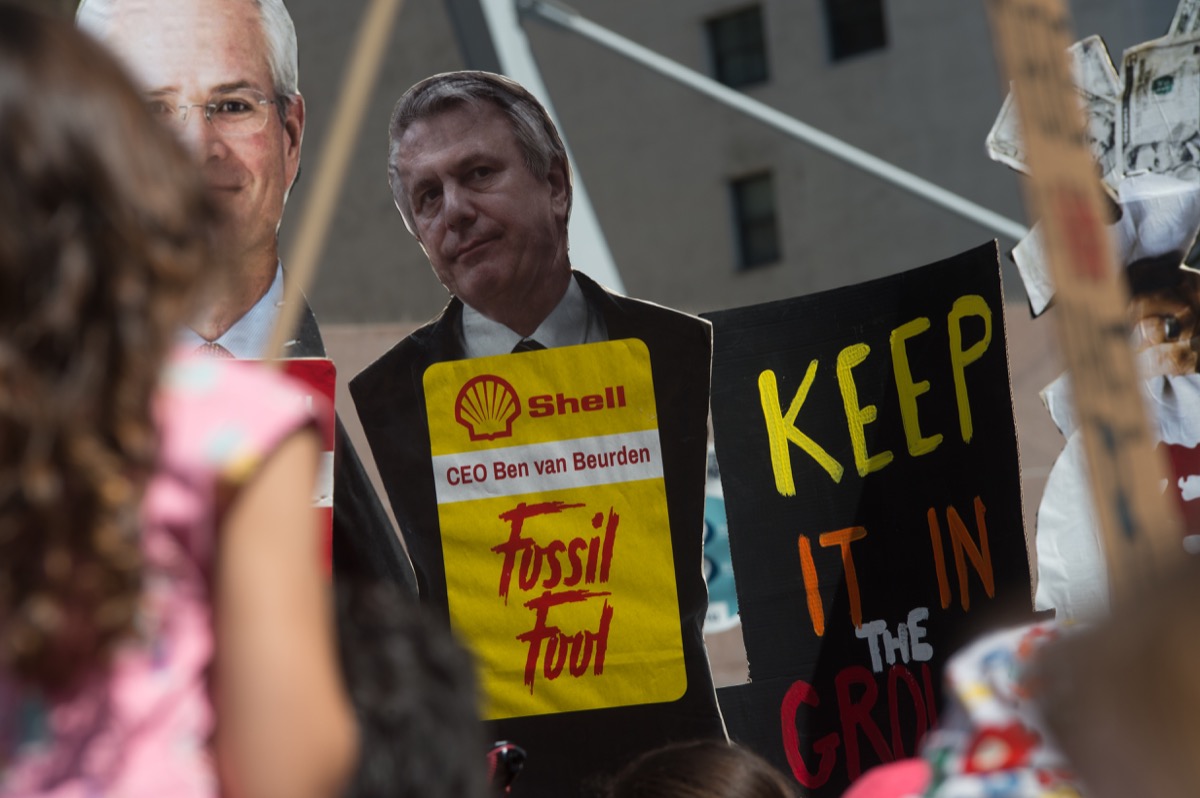

There will always be a new study with some flawed assumptions to keep us all busy and we could rebut these until we all drop. The advantage for the oil and diesel industry is that articles and reports, however poor, keep the controversy alive. Discrediting or distorting science is a political strategy, as Naomi Oreskes chronicles so well in Merchants of Doubt.

True enough. But in the real world the argument is over.

The intrepid English inventor Thomas Parker shows off his 1883 electric vehicle, fully 25 years before the first Model A rolled off Ford’s factory line and settled the electric vs. fossils question… for the time being.

Buy a Car Like It’s 2036

Consumer Reports reports that today’s cars will last an average of eleven years — and, with love, fifteen. So the ethical calculus has to factor the commitment of the earth to fueling the car you buy not just now, but also until 2036 or even later.

That’s right, your new Camry or Camaro still could be pulling up to the gas pump four presidential terms from now — by which time we may have shifted the grid entirely to renewables. With solar and wind continuing to wildly outpace fossil fuel development, by then we may not be drilling for oil for any purpose other than specialty plastics… and to keep obsolete cars alive.

The electric-vs-fossils decision is nothing new. Electric cars were being developed right alongside internal combustion vehicles across the early history of horseless carriagery. In the end, it wasn’t ethics that made the fuel decision for us, but the discovery of plentiful oil.

But today, the decision is very ethical and it’s a clear one.

Buying an electric car is the demonstrably “greener” personal decision. But larger than that, it sends a message to the auto industry that consumers are moving forward. It sends a message to government at all levels that it is time to invest in infrastructure around EVs, and start dismantling the massive, subsidized global machine we’ve built around petroleum.

And finally, perhaps, buying an EV is a “gateway” decision, which gets each of us individually thinking about how we can continue to green up our lives. If we have an EV, can we go a step further and build it a solar carport? Can we go a step further from there, and streamline things so the solar carport serves all our power needs?

Don’t get us wrong. Buying new stuff won’t save the world. But good decisions, in a larger sense, will. Something as impactful as the engine in your car needs to be a good decision.

Glocal Warming, Glocal Response

It can be hard to conceive of an issue as big as climate change. Global warming is, after all, global — geographically but also as an idea. Reflecting its sprawling unknowability, some environmentalists like to say “think globally, act globally.” Others use the invented term “glocal” to describe a phenomenon that’s both planetary in scale and also felt and fought locally.

Still others — especially those themselves impacted — address the problem as purely locally as they do the rest of their lives.

Global and local issues can be hard to tell apart. Here in Los Angeles, for instance, some apartments come complete with an oil derrick in the backyard — a striking image, though not one as well-known as the Griffith Observatory gleaming above the city’s palm-lined boulevards. Those relentless derricks are “glocal”: if we can rid the world of its giant pipelines and massive oceanic wells, we’ll rid our neighbors of this too.

Los Angeles, with its population of 3.99 million, is “the largest urban oil field in the country” and the cultivation of both crude oil and natural gas within city limits makes toxic airborne gases a persistent part of the local climate. Of course, this mixes with transport exhaust that’s still so thick that the 710 freeway corridor connecting downtown Los Angeles and Long Beach is known unsentimentally as a “diesel death zone.”

You’re likely to hear us old-timers say that “the smog’s not as bad as it used to be.” Yet toxic air is as persistent a problem as ever, and as fluid as air is, the impact is not felt equally by all 3.99 million of us.

The climate is indeed unjust. The direct relationship between being black or brown and the likelihood of living in areas with toxic air or water is well documented, and so the direct connection between being black or brown and higher incidence of Covid-19 is not surprising.

As bad as a “diesel death zone” sounds, living in a “sacrifice zone” sounds even worse. It rings an especially resonant note of injustice in the voice of Jasmin Vargas in KCET’s hourlong documentary Power and Health, as she tells her part of the story of how power influences the collocation of people’s homes and workplaces and deadly environmental toxins.

Her fight is indeed a local one, but it is a mirror of those we all need to wage together. Whether our focus is on energy or trees or plastics or geopolitics, the work needs to be simultaneously happening at all levels, from the most personal to the most political, from the most local to the most global.

Those who aren’t fighting a battle for their own family or community can follow whatever mantra is most inspiring: think global act local; think local act global; think local act local; think global act global. Our purpose can be found wherever it comes naturally, but the secret lies in a different, nonsense-free mantra: in just do(ing) it.

The affluent aren’t immune from local impact of a global problem: burned trees and a houseless chimney at Tigertail Road after the 2019 Getty Fire, January 2020. Mount Saint Mary University’s Chalon Campus in the middle ground was spared from the blaze, but its students won’t soon forget their “harrowing” escape.

(Up top: Oil derricks and a new apartment building in south Los Angeles, April 2020. The resemblance to grazing dinosaurs is perversely poetic.)

“Net Zero by 2030”

This feels like momentum, folks.

The Guardian: “Three-quarters of Australians back target of net zero by 2030, Guardian Essential poll shows.”

Must each of us witness destruction like Australia has seen before we reach this conclusion… or have we all seen enough?

Net zero by 2030*. If we want to survive in a world that’s something like the one we live in now, we must all be like three out of every four Australians, and demand nothing less than that.

And then work our dingoes off for it.

*For more info about the actions we’ll need to take to reach net-zero by 2050, please see the IEA’s new “World Energy Outlook 2020.” It’s strong medicine…

This Holiday Season, Let’s Give Shopping a Gift of Its Own: A New Purpose

All the days following Thanksgiving celebrate our prodigious gift for shopping. “Black Friday,” whose name dates back to 1966, is followed by the newly minted “Small-Business Saturday” and then a quiet pious day to get rested and prepared for “Cyber Monday.” That’s the day you’re supposed to continue fueling the economy while on the clock at your job ostensibly doing something else. “Giving Tuesday” stands at the end of the line, ringing its bell and giving you the guilty side eye after all this consumerist bacchanalia.

It’s easy enough to sigh in anguish, á la Charlie Brown, about the rampant consumerism, but a little empathy may be in order too. After all, for a stressed-out, disconnected, compromised human organism, shopping is a dopamine-triggering easy pleasure. Through the 20th century, it became the way comfortable modern people in comfortable modern societies expressed their comfortable modernity. By now, shopping is such a native skill that we interpret much of how we experience our world as acts of “consuming” and “collecting.”

Left: 1918, watching Santa climb from his parade float into Eaton’s Department Store, Eaton’s Santa Claus Parade on James Street, Toronto. Right: 2008, iconic image from just prior to a shopping stampede at a Long Island Walmart, which killed one shopper and injured four others, according to the Black Friday Death Count. (Eaton’s / Augustine for News)

The 21st century added to the recipe: plentiful plastics, round-the-clock R&D, disposable LEDs, 24/7 marketing, microchips as cheap as potato chips, and a competitive international labor market. So today, we consume all products as consumables. We consume everything as if it’s disposable. We’re a big machine for converting raw materials into landfill.

Broadway, downtown Los Angeles: it’s often cheaper to buy a new piano than to repair an old one… so we mine some new metals and harvest some trees to keep the music playing in the drawing room. But what’s to become of the family heirloom?

That said, if the 20th century turned human beings into consumers, it’s not the worst new skill we learned. And maybe we don’t need to be so Charliebrowniest about something that is, after all, a skill… and a big chunk of the economy. Maybe it all just needs a new purpose.

Shop ’til We Drop — for the Climate?

We climate evangelists are supposed to preach against consumerism, but the message isn’t that simple — since many climate solutions seem to demand that we make and buy new things.

In fact, climate mitigation is shaping up to be an orgy of consumerism. To turn the page on internal combustion, everyone’ll be buying new electric or hydrogen cars, motorcycles, trucks, scooters, and whatever people-movers come ’round the corner next. To transition from natural gas, we’ll scrap our gas heaters, water heaters, and stoves, and head out to buy new electric models. To clean the grid, we’ll cover all our roofs with solar panels and mount giant batteries on the wall to compensate for unsteady photovoltaics and wind turbines.

Those photovoltaics and wind turbines will need unprecedented volumes of new metals and minerals. Plus, depending on whom you ask, we can’t forget to swing by the uranium shop to fuel the new fleet of little modular next-generation nuclear plants that will help break the natural-gas addiction we’re now acquiring.

In other words, it’s time to shop ’til we drop… for the climate! But it means rethinking the rest of our shopping, and the 69 percent of the U.S. gross domestic product that it represents.

Do We Even Like Our Toys?

According to research (of which here is some), we’ve been giving babies and toddlers toys they like less and less with every passing decade. If given a choice, babies and toddlers will reach for simpler toys with logical feedback over complicated plastic items that do unpredictable things like bleep and flash. Generally, young children prefer things like blocks, bowls, and natural materials to the latest plastic branded product. Babies get seemingly endless satisfaction from testing Newton’s laws of motion with easily conceived, tactile objects. And, if given blocks they can stack, they can do things like collaborate at much younger ages than expected. In other words, kids like simple, natural toys better, and those toys are better for them.

As for the rest of us, it’s fair to ask ourselves whether we like our toys as much as we think we do. For one thing, if we like our things so much, then why do we constantly replace them? To paraphrase the Grinch, maybe satisfaction “doesn’t come from a store.” How many bottle openers do we need? How many place mats? Bungee cords? T-shirts commemorating our every achievement? Outdoor speakers shaped like rocks? Stuffed animals? Does everyone in the neighborhood need a ladder that we use once or twice a year? How frequent must be our new televisions, computer monitors, tablets, bluetooth speakers, and all the wires that tie them all together?

What do we really want to play with? How about the time we would gain from not working to buy more things? How about experiences? We’ll leave these bigger questions for another time.

Santa Monica Salvation Army: STUFF. Formerly raw materials peacefully stored in the earth’s crust; then, dopamine-inducing purchases; then, awkwardly waiting to be sorted on the way toward the landfill. As for the bale of clothes at the bottom — the average American throws away 81 pounds of clothes a year. Empathy stops here. This has to stop.

Sacrifice?

Moving into the coming phase of climate action, climate communicators tiptoe around the word “sacrifice.” Is this a “war footing” we’re going to be on, where we need to ration butter and turn in our extra ladders to be melted down into offshore windmills? Or, is it a man-on-the-moon effort requiring of the public a lot of cheerleading and modest behavioral changes?

If we all agree we need to reach “net zero” by 2050 (we do), and have to get perhaps halfway there by 2030 (we do, because the other half will be more difficult and require twice more time), how do we approach the easy sacrifices (“I no longer need a commemorative t-shirt every time I attempt a half-marathon”) and do we approach the harder ones (“I can no longer eat food that pleases me”)?

A Clue from Covid-19

In this month’s Foreign Policy (subscribing online-only now for the climate!) Max Ehrenfreund reported a clue in the economics of American survival during Covid-19 — “The World’s First Affluence Recession: The pandemic is making Americans poor—precisely because of the way they were rich”:

The modern economy has been immune to infectious disease—until now. Epidemics in the modern world have ruined hopes, debilitated bodies, and claimed tens of millions of lives. This [is] the first epidemic in American history that has also caused an economic crisis. Between April and June, about $2 trillion of economic activity in the United States came to a halt. Adjusting for changes in prices, that was nearly one tenth of gross domestic product. Even though public-health authorities and ordinary people took similar steps to stop past epidemics from spreading, none had remotely comparable effects on the economy—not cholera, which struck repeatedly in the 19th century; not the fearsome bubonic plague, which visited San Francisco in 1900; not even the so-called “Spanish” influenza that arrived in the United States in 1918 and killed tens of millions internationally.

What has made this pandemic unique is that for the first time, consumers worldwide can afford to spend a significant share of their incomes on non-essential goods and services. Much of their consumption has become optional, and rather than risking death to buy a Frappuccino, they’ve chosen to stay home. Others would like to go out, but public-health authorities have ordered non-essential businesses to close. Because the discretionary share of consumption has expanded, the choices about non-essential business that governments and individual consumers make in response to pandemic disease have become an economic problem.

The shift in the makeup of economic activity is due to decades of transformative economic growth. Previous epidemics did not cause economic crises because most consumers were poor by today’s standards, and their discretionary spending was minimal. The overwhelming demand for necessities such as food and clothing, which neither households nor governments could restrict in the interest of public health, kept the economy going. Today’s economy depends on a thousand luxuries large and small, from overpriced coffee to air travel, and these luxuries are what many consumers are now giving up. Willingly or not, they are saving instead of spending. Extreme savings rates are a defining feature of the available data on the coronavirus economy.

The public-health crisis is the result of a novel pathogenic coronavirus. But the economic crisis is a result of our affluence. Growth has created both extraordinary prosperity, and previously unknown risks.

(Quoting excessively because there’s considerable guidance here.)

So, how much disposable income is disposable in trade for our future?

How shall privileged humans spend money and time for the rest of this decade? How shall they act for the next three decades while we bring ourselves back into harmony with the earth that sustains us? How shall we choose to design a future that features the luxury of assuming that great-grandchildren will still be able to live with the comforts enjoyed by their great-grandparents?

We can shop thoughtfully, deliberately, and with purpose for the future we want. And, we must.

How to Organize, Organize, Organize: Step 1 – Fall in Love

The more we learn about trees, the more we understand that they communicate and share resources through their roots, recognizing one another’s needs and working toward shared goals. This might be a relevant metaphor.

It’s November 2020, and we know that humanity has just this one decade to stave off the worst impacts of climate change. We can achieve this, but the sheer scale of the problem means it’s all hands on deck.

I think people want to do something about it, but most don’t know where to begin — beyond reducing our own consumption and our “carbon footprint” (here’s 35 ways, for instance, to do that). Some people already personally impacted don’t have the luxury of not knowing where to begin. Others are already integrated into an activist community, or are veteran environmentalists, or have an blue-ocean idea that inspires them. Some have have a relevant Ph.D., some have an audience of millions they can influence. But what about the rest of us who know we want to roll up our sleeves but not how?

These days on Zoom, one answer you hear a lot is “organize, organize, organize.” But for the non-organized among us, what does THAT mean? It means simply to hook up with an existing organization, cause, or group that really speaks to us.

Unless you have massive resources to spread around, it’s a good idea to choose just one org that makes you swoon. Treat it like dating — do your research and be discerning, because there are a lot of fish in this sea. A lot of good fish, too. If you choose one and find it doesn’t inspire you, drop it. Find another, or in the end… you won’t end up engaged.

Aim for butterflies. It should be more than just writing an occasional check. Your match should excite you, should inspire you — to volunteer; to join or lead a committee; to help raise money; to collect water samples or monitor king tides; to take photographs, write poems, or use your social network to spread the word… to give whatever you have to give. You’ll meet like-minded people, and you’ll move forward into this decade together.

You already have a busy life — to be motivated to give more and do more, you need to be inspired by the cause you choose. One thing those of us who run nonprofits inevitably learn is that no matter how magnificent an answer we have to one of life’s persistent problems, it won’t appeal to everyone. Whether it’s emergency response, or feeding orphans, or curing terrible diseases, or rescuing puppies and kittens, some people will always be more interested in something else. Likewise in the climate space, some people will be more interested in windmills or solar for remote villages … or planting trees … or clean air and water … or protecting undeveloped spaces … or reducing consumption of plastics … or electric cars … or sequestering carbon … or replacing wood fires with cleaner fuel … or being or amplifying youth voices fighting for climate mitigation, climate resilience, and climate justice … or reclaiming copper for use in windmills … or… or… There’s something for everyone!

Global warming, as the name implies, is a global problem, and different solutions and amazing ideas are cropping up everywhere in the world. Pour yourself a cup of something, and ask your friends or neighbors if there are local efforts to join. Or, try jumping into any of these “dating” sites to get started:

- The Climate Coalition

- Medium/Thales Dantas: “Organizations Fighting Climate Change: A Quick Guide”

- Vox: “Want to fight climate change effectively? Here’s where to donate your money”

- NAACP: Climate Justice and Environmental Organizations

- Vice: “12 Environmental Justice Organizations to Donate Time and Money To”

- The U.S. Climate Action Network

- UNICEF: Youth Action

- List of Accredited Organizations by U.N. Environment

- State of California: “List of Worldwide Scientific Organizations that hold the position that Climate Change has been caused by human action”

- Outdoor magazine (2016): “The 6 Best Environmental Groups to Donate to for a Better World”

Get carried away by the search, keep trying, don’t be afraid to fail and start over, and finally, let yourself get carried away. Because if you don’t, you might someday wonder how you let the years go by without it.

And then one day, this decade and its promise will be gone.

Even “If Washington Is Lost”: We Now Know How to End-Run Federal Obstructionism, Anyhow

Sunrise, Penn Cove, Washington: every new day is another lesson in resilience.

For the climate, last night’s unresolved elections in the United States couldn’t have higher stakes: this January, one of the world’s biggest energy and environmental policy stakeholders will either be demonstrably hostile to science and climate action, or committed to spending $trillion$ to guide climate adaption and mitigation.

But even amid the election chaos, I’m reassured to know also that during the last four years, climate creatives in the form of smaller nations, U.S. states, organizations, and individuals have innovated in yet another way: learning how to do end-runs around an obstructionist U.S. government.

Great read in Politico

Until we know the election results, you can get some comfort from Monday’s article in Politico, which was profoundly reassuring despite its apocalyptic title: “The Environmental Movement Braces for a Second Trump Term.”

As Karl Mathesien writes, after having failed to prepare for the Trump administration, we are now much better prepared to meet U.S. obstruction as we face one final decade in which we can make a significant climate difference:

In the U.S., environmentally conscious youth are preparing for war. But also admitting that fighting the administration on climate directly won’t be their goal. American climate activists are battle-hardened, allying with wider social justice and anti-racism campaigns and taking nothing for granted, said Henn. “We’re hosting mass trainings on how to prevent a coup, planning efforts to go after Wall Street if Washington is lost.” Other groups expect court battles to feature heavily, despite a broad conservative shift in the judiciary under Trump.

Luisa Neubauer, a German activist with the Fridays For Future movement, said European leaders would also feel more pressure if Trump wins. “Wherever the U.S. fails to reduce emissions or finance climate mitigation, other states have to make up for that — that’s how a collective crisis works. It’s more work for everyone.”

Groups that lobby through international diplomacy, like the ECF, will focus on isolating a Trump-led Washington by encouraging other countries to simply move on.

Please read the article, and our own post here, for more climate action energy and a lot of links to more.

And remember, every setback is yet another lesson in resilience: because if we’re going to succeed, our first duty every damned day is to wake up focused and positive and a little bit more aware of how to defeat those who stand in our way… or to just ignore them and move on.

More Cause for Optimism: “We’ve Had So Many Wins”

Without permission but with gratitude. Click to read about the Guardian‘s climate pledge, which is good journalistic leadership for a world with a hard deadline.

Last month we wrote about the importance of optimism as the global community prepares to tackle climate change in one decade.

In that spirit we present this Monday’s article in the Guardian: “‘We’ve had so many wins’: why the green movement can overcome climate crisis.”

It’s a quick reminder of many of the often unheralded successful precedents of the environmental movement. These include the global end of “leaded” fuel, the international rescue of the ozone layer, the end of acid rain almost everywhere.

The older among us will remember that these problems seemed hopeless at the time. But, writes Fiona Harvey, the global community solved them anyway:

It is easy to forget that environmentalism is arguably the most successful citizens’ mass movement there has been. Working sometimes globally, at other times staying intensely local, activists have transformed the modern world in ways we now take for granted. The ozone hole has shrunk. Whales, if not saved, at least enjoy a moratorium on hunting. Acid rain is no longer the scourge of forests and lakes. Rivers thick with pollution in the 1960s teem with fish. Who remembers that less than 30 years ago, nuclear tests were still taking place in the Pacific? Greenpeace’s Rainbow Warrior ship was blown up by the French government in 1985, with one death and many injuries, in a long-running protest.

As well as giving heart to activists now, these victories contain important lessons. “The environmental movement has been very successful,” says Joanna Watson, who has worked at Friends of the Earth for three decades. “We’ve had so many campaigns and wins. Sometimes it’s been hard to claim success, and sometimes it takes a long time. And sometimes things that worked before won’t work now. But there’s a lot we can learn.”

We should all nail this article to the wall where we can see it. What can inspire genuine optimism better than a perpetual reminder that, when we’ve had to, we’ve succeeded before?

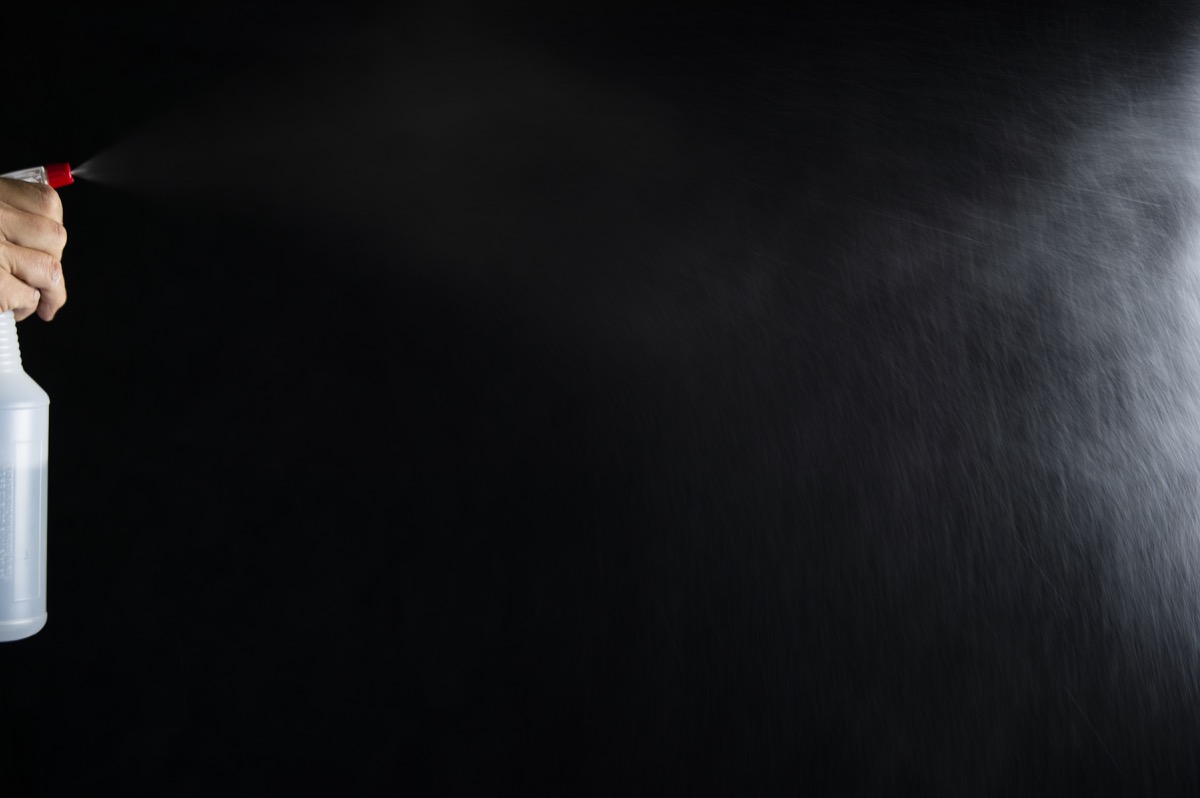

Humanity put its mind together and concluded that we simply did not need chlorofluorocarbons to evenly distribute liquids — and so we didn’t have to sacrifice the ozone layer for convenience. In fact we didn’t have to sacrifice anything at all. Here, in our informal analysis of aerosols, a dime store squirt bottle delivers a nice, even distribution of water at a light source one meter away. (Squirt bottles remain a better solution than pressurized cans even without the CFC factor — see this 21-year-old artifact for still-current info.)

What Connects Us All If Not Our Climate?

As we noted a few years back, this is the century in which humanity will re-deepen its relationship with its surroundings. The reality is, we’ll either have to do this consciously and deliberately, in the process of extricating ourselves from our climate peril, or we will reconnect inadvertently and reactively as we learn to live on a diminished planet with an unfamiliar and hostile climate.

Certainly for some, the pandemic provided an instructive opportunity to slow down, pay attention to the natural world, and get connected. Today, as we write these words, the California pepper trees in our front yard are providing just that kind of opportunity. Though it’s not spring, they are in blossom now and a welcome source of non-political conversation on our street.

Did you know that every single peppercorn that ends up in your pepper grinder starts as a blossom? Every year those minuscule yellow flowers explode in clusters and turn the trees into resonant bee clouds that buzz for weeks. Young parents on the sidewalk wander right into it, then flee across the street behind their strollers. But they’re in no peril — these bees are obsessed with their work and seldom rest long enough even to pose for a clear photograph.

Our old posts on California almonds and white clover got us thinking about the precarious condition of the honeybees — the farmed ones and the wild ones, respectively — and how tied that species is to us humans. Farmed and wild bee populations may or may not be the equivalents of our salaried workers and independent contractors, but either way their labor is just about as big business as that of their human counterparts. Honeybees and other pollinators are responsible for perpetuating 70 percent of the world’s food crops. Alone, the aforementioned almond farms of California’s Central Valley require the labor of half of the honeybees in the United States.

To say the least, wherever go the honeybees, we go too. And so it is with the oceans, the soil, the rivers, the atmosphere right up to the Karman Line, the entire food chain from the tiniest insect to the largest lion… and one another.

(An observation hopelessly kumbaya not long ago. Today: life and death!)

While human connection may seem like an especially hopeless aspiration at a time like this, on the other hand, what connects us more than the climate? What connects us more than the air we breathe? Our giant air bubble connects every demographic with every other demographic. For instance, in China’s smoggiest years, citizens consoled themselves, mostly accurately, that their leaders, for all their luxuries, had to breathe the same air they did. And indeed, China invested trillions to claim global leadership in energy technology to move us all beyond dinosaur fuel, and indeed the lungs of all China’s economic strata are reaping the rewards. For that matter, so are ours outside China as the cost of solar plummets and more of us are able to make smart climate decisions as a result.

No one is immune to bad air locally, and no single country is immune globally. Neither is any nation wealthy enough to solve the crisis by itself. What do all 7.8 billion of us humans share, if we don’t share the climate systems that roll over countries and cross borders with the ease of post-internal-combustion engines blowing by mileposts? What can bring us together in all our diversity, if not a shared investment in a healthy climate with its byproducts of healthy oceans, recognizable seasons, and familiar latitudes and longitudes?

Bees Aren’t Distracted by Human Abstractions

If we’re going to get this done — and the 2020s are the last decade in which we can — we need to move past both nationalism and globalism, isms that divide and separate. We need to ditch those isms in favor of building new intra-human neural pathways for the kind of collaboration that will be necessary for us to confront the challenges ahead of us: challenges that care as little about borders or other human abstractions as do these honeybees who remain so fixated on their work… with utter disregard for whether they’re in Canada or the United States, or in Luxembourg or Belgium, or in North or South Korea, or in Kashmir or any part of Cyprus.

These here bees are as un-national as any migrating bird. They don’t care. They just get it done. Like we now have to.

The era of globalism brought the honeybees habitat devastation, indiscriminate global pest control, wild climate fluctuations, varroa mites and other bugs of all sizes, and whatever other factors cause colony collapse disorder, and the bees carried on with their work anyway. By contrast, we looked at factors like the widening gap between rich and poor and allowed the toxicity of nationalism to seep back into the human condition.

The rise of nationalism on a scale of all humanity wasn’t a bump in globalism’s road. Globalism is an irredeemable wreck alongside the aforementioned highway of history. Yes, the trade-connected globalist world had its benefits (unprecedented global prosperity and stability among them), but it was a cold and mechanical relic of the 20th-century industrial and post-industrial mania for growth. In the end, the 2016 crippling of the Trans-Pacific Partnership shed a harsh light on a United States divided largely by economics, a Europe in danger of unraveling for the same reason, and an ascendent China whose belts-and-roads moneybag diplomacy had nonetheless reached its peak. Small countries had not failed to notice their enduring marginalization any more than the poor in the “developed” economies failed to notice the rich pulling further ahead with every year.

And so the people reacted with the tired flags and stale ideas and dead language of nationalism, supporting anachronistic leaders like Trump, Duterte, Bolsonaro, Erdoğan, Orbán, and Modi, along with Putin and Netanyahu in their resilience. Meanwhile Europe’s softened borders — truly a monument to connectedness — began to harden once again.

Unsurprisingly, the world has not profited from these old-fashioned leaders with flag-waving and border-closing ideas — what solutions have they contributed in any meaningful way to twenty-first-century problems that all transcend national borders, with climate change just one of many?

The financial integration of globalism was not necessarily a bad thing. The problem was that the objectives of globalism were fundamentally financial, and the goal growth at all costs. International cooperation wasn’t happening at the barrel of a gun, but it did have strings attached — it was international inclusion with interest, kept aligned by a bottom line measured in GDP, but also driving a poverty of ideas, of populations, of species, of climate.

Globalism as we knew it had outstayed its welcome. But nationalism was not the replacement anybody needed.

If Globalism Is Dead and Nationalism Is Toxic, Do We Need a New Ism with Purpose?

Can we just get rid of these giant systemic isms without replacing them with another? For sure, labeling something is a great way to rob it of its meaning. On the other hand, perhaps a new ism could be a bugle cry as we aspire toward common goals of a scale that we have never needed to reach before.

Globalism is in fact dead, but what killed it wasn’t so much the way the financial system was structured, or the way rising debt has created financial activism, or even specifically the rising chasm between rich and poor (to use Michael O’Sullivan‘s three-pronged prognosis). Rather, once the financial system had integrated about enough as it ever would, the culprit that killed globalism was a lack of a specific defining purpose.

And if global warming gifts us with anything, it gives us purpose.

The new guiding ism could speak to knowledge, ideas, and resources that do not have their roots in any one country or population, or even, indeed, in humanity itself. The idea of survival in a changing climate is so vast and so universal that it renders meaningless not only borders, but also the way we think about ourselves separately from our natural context. And so, internationalism, for all its historical positivity, may keep too much baggage in its nation trunk. So then you have history’s other charming ism — cosmopolitanism, with its “citizens of the world” connotation. Cosmopolitanism has the benefit of sharing a root with cosmos, but it does have the baggage of sounding like a specific, unhelpfully urbane, human category.

Recognizing the integration of our fate with that of the bees, maybe the ism should rise above the human community altogether, relating us instead to our larger context. An ism that could speak to a single collective aspiration so large it exceeds humanity, a word so large it exceeds even our earth with its complicated systems, that pulls the camera back past the atmosphere and looks at the whole of us. Something… almost… super-religious in its scale. Got one?

Universalism, a word from religion, speaking of all religions, looking from that perspective beyond religions. An ism beyond human categories — all fields, all demographics, all karasses — ditching the categories and so eliminating the friction between us and a livable future.

If we become univeralists, and act with universality, then if there is a new way of building a dam, more efficient than the old kind of dam, better for the fish than the old kind of dam, then the rivers themselves should have it.

If we act with universality and a smokestack can be replaced by a thousand inert, carbon-neutral solar panels, the downwind area must have it and the ten thousand labor hours must be invested to decommission one and install the other.

And if we are to be universalists and there is a way to restore coral, or put carbon back underground to improve soil and cool the earth, then the soil itself, the earth itself, the coral itself, the ocean itself, and humanity itself, should all work together and have it.

We’re probably not going to haunt the halls of the UN or CNN to lobby for universalism, but we present it here in the spirit of brainstorming. Whether it is unifying ourselves under a mind-opening ism or dumping the abstractions altogether, we must do whatever it is takes to connect with the world.

Because if we are really paying attention to something, like these bees and their blossoms in these trees here, we connect them to ourselves, consider their future as one with our own, and we must act.

“We Only Have a Decade” vs. “We Still Have a Decade!”

Consensus now is that we have a decade to do what needs to be done. Is that a catastrophic problem or a thrilling opportunity?

First, what needs to get done? Yes, we have missed the chance to keep everything as it was when our parents were children and frolicked in pristine meadows and swam in unspoiled cool waters. Lost glaciers are not coming back, rising waters won’t recede, extinct animals are not waging a comeback.

BUT. Scientists tell us it is NOT too late for us to halve our carbon output by the end of this decade, and strategically create paths to (a) end the burning of fossil fuels and (b) reduce consumption and waste and generally take care of a planet we have been emotionally distancing ourselves from for so long. This can forestall the worst of the projected impact of global warming.*

*For more, please see this key IPCC report (summarized) on the projected difference between +1.5°C and +2°C.

This consensus formed the backdrop of this week’s Global Philanthropy Forum, whose theme was “Facing the Future — a Changing Climate in a Changing World.” It warmed some cold and callused hearts to see the whole philanthropic community gathered (albeit digitally) to discuss a massive existential crisis which, not too long ago, could escape mention in even the most comprehensive global development meetings.

Even more exciting to this attendee was the sense of optimism that pervaded just about the whole proceedings. (Optimism is NOT common in very many conversations about climate change — least of all at this level!)

From the Global Philanthropy Forum, with gratitude. Cute infographics are easy, but these reflected actual flow of ideas.

Right from the top, Christiana Figueres, the Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, and Aaron Bernstein of Harvard’s Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment not only advised a strategic moratorium on “doom and gloom,” but also were authentically not doomy-and-gloomy themselves. Figueres pointed out that, at last, “the economics are on our side,” as zero-carbon energy sources become as cost-effective as burning fossils, and as funders gather to put economic power behind something that has been so underfunded for so long. Bernstein pointed out that climate change is actually one of the rare instances in global policymaking where we actually “understand the problem and we know what to do about it” — a resonant message.

These are some very optimistic perspectives, and they’re welcome, since, as Aaron Bernstein said (and I’m quoting loosely), “it’s almost irresponsible to focus on the problem, on the doom and gloom, because it makes people complacent.” In this, it’s nice to be in the company of such luminaries who have been working for so long not only at developing and promoting solutions to the problem, but also figuring out ways to communicate it — sometimes with very few listeners. Even Bill McKibben, who wrote the agonizing, essential The End of Nature, gets more hopeful every time I hear him, and his 350.org seems to be fueled in large part by hope. He speaks of “cramming the work of four decades into one decade,” but in a tone that conveys he thinks it isn’t impossible.

Some of the projects and perspectives from the conference will inform later posts here, but for now we’ll conclude that the conference was arguably unified in its key take-away message: We have one decade to do what needs to get done — but from a practical perspective it isn’t unrealistic. If we stay focused.

Yes, we can do it because we need to believe we can in order to do it. But we also have a head start, thanks to so many committed individuals and organizations the world round. And, as this conference illustrated pretty clearly: we’re just getting started.

This way of attending a conference is a CLIMATE WIN, and it illustrates how we can realistically adjust human behavior to forestall and adapt to climate change. Gone — at least for now? — are the flights, buses, taxis, diesel-chugging boat cruises. At the end of the proceedings, we simply said goodbye and closed the computer. It may not be as good for making friends and late-night brainstorming in the hotel bar, but it is a great time for people who want to attend a fascinating and rewarding conference while simultaneously observing the behavior of honeybees in a blooming California pepper tree. That’s us.

The Answer to Everything.

We’re just going to lay our hand on the table right here and right now.

This morning we are reading the World Wildlife Fund’s “Living Planet Report 2020: Bending the Curve of Biodiversity Loss,” which in the WWF’s words:

“provides unequivocal and alarming evidence that nature is unravelling and that our planet is flashing red warning signs of vital natural systems failure. The Living Planet Report 2020 clearly outlines how humanity’s increasing destruction of nature is having catastrophic impacts not only on wildlife populations but also on human health and all aspects of our lives.”

Yes. So, blog-that’s-trying-to-figure-out-what-we’re-supposed-to-do-about-climate-change, what are we supposed to do about it?

Just this, and only this:

We must refocus every human life toward solving this problem, all the time. Right now.

Hard work and sacrifice toward a better life — not just a better future life, but a better life right now.

If you’re one of those people who has taken to blaming 2020 for what we see around us, you no doubt know what I mean. Because the 2020 everyone is complaining about is actually us. You and me. The collective achievement of all 7.8 billion human beings spread out on this planet.

2020 is us; it’s ours to own. It’s what we have made of ourselves. And if we can own it, we can come together to fix it.

Perhaps this is what they have been trying to tell us all along.

The single answer to all of our problems is a single, shared, common purpose.

The single answer, more specifically, is to do the following:

First, every human being on earth with the slightest bit of emotional space needs to look around at what it means for the planet’s biodiversity itself to be gravely endangered by our actions. For the animals’ and plants’ own sake, for the sake of the planet as a whole, and only lastly for our own sake if we like to eat, drink, breathe, and exist in our beautiful world.

What does it mean for the bugs to be gone? What does it mean for ecologies to die?

What, well beyond our sympathy for or sentimentality about polar bears, do these painful losses mean about who we are and what our future holds?

Then, we need to stop doing everything destructive, forever, and replace it with everything constructive.

Does that sound hard? It shouldn’t be. Not if we take a fresh, clear look at what we want to make of whatever time each of us has on earth.

What does everything destructive mean? It means much more than some cartoon-villain industrialists mining away terra nullius, untouched wilderness, or ripping down an old-growth forest for a new factory.

Nope. Destruction is everyday life. Destruction is in everything we do, and to stop it means first ending a thing that defines who we are collectively. It means tearing the idea of “economic growth” out at the roots, and with it our instinct for perpetual expansion — a survival instinct that is threatening to kill us.

Paradoxically, this most challenging part should not be laborious. To replace a failing act with a nourishing one takes resolve but should not be painful. Our addiction to growth is not biological; it’s psychological, and so there will be no delerium tremens.

If we can let ourselves reorient ourselves around reducing the footprint of a good life to its smallest possible size, the actual act of doing so should be easy, as it speaks to doing less work. It speaks to a notion of enjoying our time more. It speaks to leveraging the effort that we do make, to consciously building each other up so that the primary profit of our hour of work is time.

But rethinking economies and labor for survival now does mean doing hard things. Harder things than we have ever done before. It means sacrifice. It means that every job that now expands our footprint on this tiny planet must be replaced by a job reducing our footprint on this planet.

It means all humanity looking critically at what we have and what we make, and committing to replacing consumption with preservation wherever possible.

It means those who profit most from the everyday destruction must make the most sacrifice. That is not the redistribution of wealth — it is an equitable sharing of responsibility, and furthermore it is a cost/benefit analysis no different than any other.

Because no major corporation stands to do well in the smoldering ruins of the world in which they grew and prospered.

Finally, the answer means thinking and speaking in new ways.

Capitalism, industry, economy, government, unions: these are our tools. We need our tools to do the work. But the work needs to be bent toward new goals.

We need to change not the tools but the goals of the tools — for instance, from “economic growth” to “the preservation of a good life” — and then achieving the goals.

Is that so hard if we set our minds to it?

What does it mean to replace old goals with new ones?

If our new objective is not growth, but rather the preservation of our good life, we permit ourselves to make difficult observations — such as, that the consumption of raw materials is an “evil,” if sometimes a necessary evil, and that the value of everything we do has to be balanced against it.

It means all R&D and development right now and forever need to be analyzed first for how they preserve and restore the planet that sustains us now, that we expect to sustain the precious children we are now having, that we expect to sustain our precious grandchildren, and that we expect to sustain our precious great-grandchildren and those beyond that.

Grandchildren and great-grandchildren may sound unrealistic in 2020, but it doesn’t have to be unrealistic. If we want a world that includes great-grandchildren, we have to the work for it. That’s all.

This means every hour of every job needs to be looked at first for how it impacts the future of the system of biodiversity, locally and systemically. We have to measure and rebuild this economy with that as the first goal, and profit second.

We need to decide what kinds of occupation do we not need at all. What jobs simply create profit from economic growth? What jobs do we do now just because we have always done them? Which are focused on the growth of wealth, the growth of the human footprint which cannot continue if we mean to survive here? What innovations and entrepreneurial efforts really just race us further toward meaningless and destructive consumption and materialism for the sake of consumption and materialism?

What is the labor of excess?

Stop those jobs, repurpose the hours. A lot of the people doing them are leaders who can lead us toward new objectives of the preservation of a good life — or to be blunt, our survival. And a lot of the people providing the labor of excess recognize the meaningless of it and do it badly as a result. All of us know people like that. Some of us are people like that.

A lot of the conflict and strife that characterize 2020 are a result of working toward lost causes and against common purpose.

In this sense, to redefine our economy around our survival is actually an opportunity — for humanity, for nations, and for all of us as individuals.

This is an opportunity to find new common purpose, but it is also a chance to recognize what we love about life and continue doing what we love, in balance with meeting our new goal. We need to preserve life, but we also need to preserve a good life.

Because every single person doing counter-productive jobs now — or doing no jobs at all — represents labor, effort, and innovation that can be turned toward the preservation and restoration of the forests, the oceans, the atmosphere we need to survive. Until whatever time these things are no longer critically endangered.

We can create in this opportunity a powerful new economy with intense purpose. Like we did with the Marshall Plan. Like we once pursued the moon. Like how we just finished building a global commons of information that did not exist at all 30 years ago. Let us use as a model all of our past successes — including precedents such as saving the ozone layer — to build an economy turned single-mindedly toward the restoration and rebuilding of these earthly systems that sustain us.

And with this, only with this, can we build a new society of hope and shared purpose, turning away from division, conflict, and a human story that has revealed itself as a species’ race to the end.

This doesn’t mean we need to stop doing everything we love. Far from it — it’s closer to taking back doing what we love.

Because year 2020 everyone loves to hate is not an aberration. The year 2020 is what we have actively done to our lives.

Replacing a race to our death with a full re-commitment to life would actually make our lives better — more hopeful, more meaningful — in the short term as well as the long term.

Because the way we were living our lives before 2020 was not providing those things. The way we have been living created what we see in 2020.

More cars; more and bigger TVs; more infernal crap in more storage units; bigger houses to fill with more air conditioning; more re-engineered food products for more marketing; more sprawl for more separation between home and work; more gadgets and chemicals to scour the nature out of our lives; more RPMs requiring more oil pumped from the ground; more disposable furniture to fill more landfills; more pesticides to do less weeding — 2020 is the crowning achievement of humanity and these are its emblems.

In 2020, we have let ourselves see that other things are actually more important: long, interrupted hours with family; digging in the dirt to make some tomatoes happen; creative and collaborative enterprises like music, theater, dance, art, and everything we passionately stream; a long, focused conversation with a friend; putting one foot or one pedal in front of the other; a new recipe and good ingredients; difficult or challenging reading; having the time to throw a ball to the dog or pet the cat. Things we have been working out of our lives for a very long time, knowing it, regretting it, not knowing how to stop.

This is how to stop doing what we already knew was wrong: we must consciously, intentionally pull ourselves together in the service of the world.

The answer to everything is common purpose.

“The Simple Act of Planting Trees Now Requires a Leap of Faith”

Fire season arrived early, and northern California is losing graceful vineyards, ancient redwoods, oaks on their golden rolling hills (sing it, Kate), and other parts of its graceful ecology. Reacting in this month’s Atlantic magazine, Leah Stokes expands upon the melancholy thinking we’ve all been doing about trees around here.

Many people have been grieving from the news that we may have lost some of the most majestic coastal redwoods to these latest fires. These giants have stood for more than a thousand years. […] For my generation, and the ones coming up behind us, the simple act of planting trees now requires a leap of faith. I worry about how long they will last before they are taken by drought or fire. And if we can’t plan for our trees’ future, how are we supposed to plan for our children’s?

Her dystopian portrait of our current moment includes power blackouts, hellish electrical storms, lethal 130-degree days in Death Valley, a looming hurricane season in the east, and misinformation from the Wall Street Journal that blamed sustainable energy for the blackouts.

Stokes doesn’t intend to scare the reader into socially-distanced bomb shelters. Instead she shows the way forward:

The CEO of California’s grid operator put it simply: Renewables “are not a factor” in the blackouts. My electric utility echoed this view in an email that urged people with solar power at home to help out. Despite electric utilities attacking rooftop-solar policy for the past decade, homes that produce extra power deliver excess energy to the grid, helping neighbors in need. More clean energy is a good thing. California must continue on the path it has been on for years: leading the world in building the clean economy. In 1978, the state set its first goal for clean energy, aiming for 1 percent of power from wind energy. Forty years later, we now have a goal of 100 percent clean energy by 2045 in state law. If anything, California must move faster. And we must get states from the Midwest to the South to do the same. The Biden campaign’s pledge to reach 100 percent clean power by 2035 exemplifies the kind of leadership we need in this time of crisis. Cleaning up our electricity system will allow us to eliminate about 80 percent of our carbon emissions, because we can use this clean power to fuel our cars, our homes, and some of our industries.

It’s pretty simple, folks: Get everything on the grid and clean the grid — and where possible replace the grid with local power generation.

And, do it right now, while we can still plan for our children’s future.

And for the future of the trees.

We lost two California sycamores here this month. It wasn’t fire this time and it wasn’t the historic drought they just survived, but was likely the two new swimming pools installed by developers within the trees’ root systems. Above ground, below ground, humans encroach. It’s what we do.

A “New Cold War” is Not a Hot Earth Option

Once upon a time, the collapse of the last fully intact ice shelf in the Canadian Arctic would have made news. But in 2020 it hardly receives notice, lost as it is in the din of pandemic, politics, protest, and the rest of the front page.

A sizable chunk of the known world can disappear unnoticed for another reason as well: it’s not surprising. It settles into world consciousness as a commonplace event among all the effects and drivers of global warming. On pretty much every latitude, in every ecological system, and from the largest country to the smallest island nation, some form of collapse is under way. It’s collectively global, ubiquitous, and systemic, and so must be the response. Though with a nod to local action, the climate response needs to be the most global and systemic work the world has ever done — progress must be integrated and leveraged and accelerated through shared ideas, technologies, and resources, counter-acting forces that also know no boundaries.

Meanwhile, today’s global politics are a cesspool of nationalism, antiglobalism, and enough geopolitical escalation that the term “new Cold War” is echoing from one foreign-policy Zoom webinar to another.

But as we approach the dreaded +2° climate threshold, all these usual geopolitics must stop, and must stop now — or rather, in these extraordinary times, we must convert all normal and abnormal conflicts and cross-purposes into different levels of collaboration.

It’s time for foreign-policy pragmatism like the world has never seen.

What Happened to 2016?

Four years ago, a lame duck Obama administration was piling on climate victories. Progress was in the air and the dragging climate policy anchor of the United States seemed to have been pulled up once and for all. Five days before the 2016 presidential election, Michael Brune, the Executive Director of the Sierra Club, penned an article entitled “Let’s Celebrate the Environmental Progress Made During the Last Eight Years” with unaccustomed optimism:

While President Obama will leave office with a climate legacy he can be proud of, the credit isn’t his alone. It also belongs to the people’s climate movement and the millions who worked to put him in office and keep him there, and then tirelessly pushed him to think bigger and do better. Regardless of who succeeds Obama in the Oval Office, we can count on at least one thing: The movement to protect our climate and replace dirty fuels with clean, renewable energy will only grow bigger, stronger, and even harder to ignore.

It almost felt like momentum — and global momentum at that — but it was not to last. President-Elect Trump, even before taking the reins, threatened to withdraw from the Paris Agreement and to dismantle the Obama administration’s energy and climate progress. Just a month after the election, Varum Sivaram and Sagatom Saha, fellows at the Council on Foreign Relations, expressed the feeling of the foreign policy community in Foreign Affairs. “If the Trump administration keeps those promises,” they wrote,

China will probably step into the leadership vacuum left by the United States. At first glance, that might seem like good news, since China is the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases, leads the world in the production and deployment of clean energy, and will probably meet the international climate-action pledges it has made so far. The trouble is that China would lead on climate-change issues only insofar as doing so would advance its national interests. Some of those interests, such as China’s desire to cultivate foreign markets for clean energy exports and curb domestic air pollution, line up with combatting climate change. Others, such as the incentives the country faces to export coal power plants abroad, could get in the way of reducing emissions. In some cases, it is unclear where China’s interests lie — for example, whether it wants to promote or stunt breakthrough innovations in clean-energy technologies. Still, one thing is certain: ceding climate leadership to China would be disastrous for the United States, whose diplomatic standing and position in the race to supply the world’s clean-energy needs would fall precipitously as a result.

If anything, Trump’s actions have been more comprehensive, destructive, and counter-conservative than promised, compromising both U.S. technical leadership and diplomatic power on a subject that is more existentially threatening with every news cycle. And the Covid-19 pandemic — though it was fun to see forgotten mountains when the smog cleared — has only set back climate catastrophe by three weeks, according to the WWF’s math. (Or, as always, it could also be much worse than that.)

As for China, Sivaram and Saha continued,

In a sign of its willingness to take over the mantle of climate leadership, China has strongly denounced Trump’s promises. Senior Chinese officials have urged the United States to uphold its climate commitments, and Beijing has pledged to make good on its own regardless of what the next administration does.

The opportunity to take over climate leadership from the United States would be a gift to China.

Though Trump’s threats were couched in defiant, virtuous rhetoric, they were and have been anything but bold; generally Trump’s executive actions have done little or nothing more than stopping work, undermining partnerships, and realizing Sivaram and Saha’s words as surely as if it were done on a plan. Trump installed reactionaries at the EPA, Interior, and Energy committed to government inaction at best, and likewise put the ineffectual Jared Kushner in charge of the crisis as a whole. In an age where every year brings us closer to the brink of climate disaster, the GOP chose to cede leadership to entities other than the U.S. federal government — with its most notable active effort perhaps being an attempt to turn back the clock on automotive efficiency, or to turn over public lands to corporations as if a conscious strategy to accelerate global warming.

China proceeded thus into the future with its mixture of self-serving and climate-forward motivations, further securing its place at the energy vanguard and influencing the developing nations in its sphere of influence. China a in the environment, sustainable energy, and related economic benefits, China has continued its disciplined environmental progress during the Trump years, accele accelerating toward its climate targets and unrivaled status as global leader on lucrative sustainable energy technologies.

More Cooks in This Hot Kitchen

Of course, climate activism and action continued elsewhere in the absence of U.S. leadership. Helping matters, the cost of solar and wind power dropped below that of coal, making it easier for everyone to make prudent climate decisions without trying to be virtuous about it.

With the U.S., U.K., Brazil, and other countries foundering in passive or regressive climate politics, others stepping forward have included outspoken vulnerable nations with everything to gain from action and everything to lose from inaction; an ever-growing list of climate organizations; and gifted individual leaders from around the world. In the United States, state and local governments have stepped forward to help fill the federal vacuum and blunt its destruction. In the corporate world, 955 companies signed the Science-Based Targets Initiative, whether for selfless reasons or out of the knowledge that climate change in the end is a threat to nearly everyone’s bottom line. And while there are more top-tens of corporate climate champions than you could ever read, the bigger news is that corporate leaders more frequently find themselves making decisions that pit their bottom lines against climate priorities. We may be seeing climate-based decisions becoming more palatable in board rooms where the financial bottom line was once the only bottom line, just as we saw companies of every stripe endorsing and supporting Black Lives Matter and quickly saw others step up to help with the global pandemic response.

This coming November, should Biden win in the United States, his administration will have much to build on. And should Trump win, the unrestrained second-term president will have at least some obstacles in his apparent pursuit of >+2° global warming.

But as far as China goes, whoever is in office must replace the rhetoric of rivalry with the promise of partnership.

Business Unusual

Sivaram and Saha concluded their 2016 their article by saying,

if Washington abdicates its leadership in the fight against climate change, it would also give up its right to complain.

Abdicating leadership cost us much more than that. With four years of coordinated action squandered, we have also ceded the right to dictate the terms of engagement. In the coming years, climate stakeholders will be pressured to distance themselves from Beijing and China-based industries due to China’s treatment of its Uyghur minority, Hong Kong policy, intellectual property, territorial claims in the South China Sea, trade disputes, the Korea chess match, and any number of future crises.

But with every year another step toward doom, we don’t have the right, or the time, to keep climate on the negotiating table with these long-term arguments. If Donald Trump has shown us anything, it’s the value of a clear roadmap — and what happens when you don’t have one. Climate leaders, whether or not that includes the U.S. government, will need to join with world leaders to forge paths of partnership that lead away from hot or cold war and toward solutions to move us together away from the climate tipping point. Though we must continue leading on human rights and regain our moral leadership, this path must not bend.

Already the European Union and others are far more likely to look at China as a partner than as a foe. Behind as the U.S. now is, it needs to follow them back to cooperative and creative global leadership on a global problem in which all our stake is the same.

Who knows, a little common purpose might help reconcile the other differences as well.

A Modest Plan for Your Review: “Rapid and Total Decarbonization of the Economy as a Whole”

Yes, ok. Global warming. It’s bad. Bad. Got it. I think I’ve got it now.

“But… what can I DO about it?”

That question is what we want to answer here. What more than just recycling, what more than buying less-damaging things, what more than reducing a carbon footprint? Rather than just make ourselves less damaging, what can we do, actively, to protract our claws, bear our fangs, tear and gnash back the damage which has now been so painstakingly documented?

But… for the most part, we as individuals can’t answer that question because as a society we can’t answer this question:

“What’s the plan!?!?”

How about this:

“Rapid and total decarbonization of the economy as a whole.”

This sounds good, and especially timely with 1.4 million new jobless claims in the United States this week, for a total well exceeding 30 million. What can 30 million people do? Well, according to Rewiring America, 25 million of them could get to work electrifying American life by 2035.

Rewiring America’s new report, “Mobilizing for a zero carbon America: Jobs, jobs, jobs, and more jobs — A Jobs and Employment Study Report” (download: Executive Summary) lays it all out, giving individuals their marching orders (buy an electric car!) but also rebuilding the U.S. energy infrastructure (and economy) before our very eyes toward decarbonizing in just 15 years. Read this report and it will be very hard to not see yourself in it somewhere, whether or not you’d fill one of 25 million jobs.

The plan starts with:

(i) an aggressive WWII–style production ramp–up of 3–5 years, followed by (ii) an intensive deployment of decarbonized infrastructure and technology up to 2035. This includes supply–side generation technologies as well as demand–side technologies such as electric vehicles and building heat electrification. […] close to 100% adoption of decarbonized technology when fossil machines reach retirement age. This is fairly simple to imagine: when someone’s car reaches retirement age it is replaced with an electric vehicle. When a natural gas plant is retired it is replaced with nuclear or renewables. […] Every American household would accrue savings of $1000–2000 per year due to lower, more predictable energy prices.

While the latter point may seem hard to imagine, anyone who has owned a recent electric car and solar panels has already seen that transportation fuel and home power combine into a larger expense than you’d think, and switching to solar power makes a big difference. This difference would be felt across the economy, and across society.

But for now, this is just a plan, perhaps a more concrete expression of the Green New Deal, but still just words on paper.

So… What Can I Do in the Meantime?

Read this plan. Critique it. Circulate it. And send it to your elected officials — Democratic or Republican — argue for them to make this part of their platform. Democrats will find it appeals to their core consituencies, while Republicans may remember that fundamentally, being “conservative” means being responsible with our resources — and if it doesn’t, we’re doing it wrong.

In the end, Rewiring America’s plan is an infrastruture plan, and infrastructure plans should be appealing across the ideological spectrum. It’s hard work to be done now in order to save resources in the future, and it’s a way this country can lead by doing.

And, “jobs, jobs, jobs”:

The transition can be done using existing technology and American workers. Indeed, work such as retrofitting and electrifying buildings will by necessity have to be done by American workers in America. No outsourcing. The jobs will be created in a range of sectors, from installing solar panels on roofs to electric vehicles to streamlining how we manufacture products. They will also be highly distributed geographically. Every zip code in America has hundreds, if not thousands, of buildings ripe for electrification in the years to come.

It is always time to write letters, staying civil, honing your powers of pursuasion. The clearer a image you can create, the more others will be able to picture themselves in it, and understand what they can do as well.

h/t Fast Company

If we had our way, we’d keep a few really beautiful artifacts of the carbon economy as landmarks. In a forest of windmills, surrounded by solar panels.

Marc Tarpenning’s Elegant Carport

Without permission but with gratitude.

We had the pleasure of attending a conference talk by Marc Tarpenning, founder of Tesla and partner at Spero Ventures, whose conference it was. While telling his story, Tarpenning showed the above slide, which we present here as a gem of simplicity.

Climate change is a confoundingly, crippingly complicated thing to talk about, and its many solutions can be just as convoluted.

Of course climate issues are complicated! It’s all tangled in an inextricable web of complex natural systems — in the soil, it the oceans, in the atmosphere, and (in the case of solutions) in the wildest aspirational bounds of our imaginations.

But this slide demonstrates just how simple and elegant can be both a solution and how we talk about it. As simple as an old windmill gently rotating next to its barn, as elegant as a water-wheel dipping into a river — representing as they do, the provision of exactly the amount of carbon-neutral power that was needed to do the thing inside the buildings to which they were attached.

With solar costs plummeting as they are, why not commit to individually powering every car (and its garage, and its lawnmower) with nothing more than the footprint of the building it resides in? Tarpenning wasn’t making that point exactly, but the slide does, and we should model as many future innovations as we can on such clear thinking and storytelling.

Windmill part of our Drought’s End tour last March.

$

In the meantime, by the way, the solar carport is a not “a thing”… but should be. Go ahead and search for “solar carport” or “solar canopy.” As with all things solar, your buying options are as bewildering and confusing as the above image is not.

Anybody who wanted to make a company to specialize in solar carports — a structure with four posts and a roof covered with solar ideally arranged to catch the sun — with straightforward marketing, installation included, systematically complying with building codes — could make a fortune, and get a lot of human mobility off the grid forever. Please do this now.