Jonathan Franzen Kicks a Beehive in the New Yorker

Without permission but with gratitude.

It’s fascinating to watch what happens when someone suggests we adapt to climate change “instead of” fighting it, especially when that person is one of this beleaguered globe’s Reigning People of Letters.

The RPOL in this case is Corrections author Jonathan Franzen, whose essay “What If We Stopped Pretending” in this week’s New Yorker declares that the time to dispense with the hopeless fantasy of preventing climate change has come. If preventing the +2°c point-of-no-return is now out of reach, it’s time to flip the switch of our limited attention span to the improvement of the lives of the people and animals who will remain on this doomed island.

Look. It’s going to be controversial to write anything at all about climate change. If “the sun is rising” were part of the pantheon of climate-change discourse, making that observation would inspire a significant portion of your listeners to roll their most ironic eyes or whip out their sharpest knives — and at the end of the day, you’d keep the sunset to yourself. But this question of adaptation is even stickier than most climate topics, and Franzen stumbles right out of the gate by setting up a rigid binary vision:

If you care about the planet, and about the people and animals who live on it, there are two ways to think about this. You can keep on hoping that catastrophe is preventable, and feel ever more frustrated or enraged by the world’s inaction. Or you can accept that disaster is coming, and begin to rethink what it means to have hope.

Why someone would reduce any complex thing to such a simple equation is beyond me. Especially a beloved RPOL, and especially in a subject where binaries (ecology vs. economy!) have been so fraught with peril for so long.

As a then-innocent planet-Earth enthusiast, I was introduced in earnest to the epic battle between climate adaptation and mitigation in a February 2007 article in Nature by Pielke, Prins, Rayner, and Sarewitz — yeah, those guys — called “Climate Change 2007: Lifting the Taboo on Adaptation.” In that article, the authors informed a bewildered younger me that in the 1980s, adaptation had been considered “an important option for society,” but that…

for much of the past two decades the mere idea of adapting to climate change became problematic for those advocating emissions reductions, and was treated “with the same distaste that the religious right reserves for sex education in schools. That is, both constitute ethical compromises that in any case will only encourage dangerous experimentation with the undesired behaviour”. Indeed, former US vice-president Al Gore forcefully declared his opposition to adaptation in 1992, explaining that it represented a “kind of laziness, an arrogant faith in our ability to react in time to save our skins.”

This seemed surprisingly combative and polarized for grown-ups working on existential problems, but as someone who’s worked in history, international development, and the arts, I’m no stranger to professional combatants who sharpen their teeth and fingernails alongside the kitchen knives. But climate change is such an intimidating subject that it forges a special spirit of conflict. So, 12 years later, here we are, still forced to argue that it’s happening at all, and as a result of this exhausting struggle under the distorting effects of the gaslights, we continue to bicker over critical issues wearily, with whatever energy that remains.

Franzen visits the Green New Deal, dismissing political solutions based on his foregone conclusion that since we have never exhibited global and resolute will to act on climate change before, we will not now. And even if we could act, we need to admit to ourselves that we have already passed the +2°c point of no return, especially considering new British projections published last month in Scientific American.

And besides, ornery Americans and others who won’t even admit there is a problem would have to deliberately sacrifice things — “Every day, instead of thinking about breakfast, they have to think about death” — so it is high time to just give up on natural and instead devote our limited cranial bandwidth to hunkering down in the world we’ve ruined.

He agrees that reducing emissions remains an ethical virtue, but:

Every billion dollars spent on high-speed trains, which may or may not be suitable for North America, is a billion not banked for disaster preparedness, reparations to inundated countries, or future humanitarian relief. Every renewable-energy mega-project that destroys a living ecosystem—the “green” energy development now occurring in Kenya’s national parks, the giant hydroelectric projects in Brazil, the construction of solar farms in open spaces, rather than in settled areas—erodes the resilience of a natural world already fighting for its life. Soil and water depletion, overuse of pesticides, the devastation of world fisheries—collective will is needed for these problems, too, and, unlike the problem of carbon, they’re within our power to solve. As a bonus, many low-tech conservation actions (restoring forests, preserving grasslands, eating less meat) can reduce our carbon footprint as effectively as massive industrial changes.

So he rejects destructive things in favor of constructive things, fair enough, but then since it’s his football he gets to choose just what kind of contstructive things to replace them with: he favors strong natural and human systems, alternate “climate actions” that will help ready us for a kinder, gentler post-apocalypse… for a time when we will sit down in the blistering heat of our resilient garden and thank god we didn’t build those renewable-energy mega-projects.

***

So Franzen wrote about climate change. And lo, social media did erupt in righteous indignation — as Vox summarizes conveniently here — for the crimes of bad science, wrong politics, and oversimplified psychology. New York magazineshares his desperately bleak vision, but takes him to task for scientific oversimplifications within the bleakness. It’s a very good criticism, since Franzen bases a significant chunk of his hopeless vision on the scientific position that since we’ve already gone beyond the tipping point, there’s no mitigating or slowing down a process that ends with the climate completely upside-down — and so, it’s time to start planning beyond recognizable natural systems and get ready to live in perpetual cyclones or whatever awaits us on the other side of the world.

Franzen’s binary thinking never lets him back on the rails, but still, he isn’t far from the mark. We do have to conduct his preferred interventions, such as “traditional local farming […] strong communities […] Kindness to neighbors and respect for the land—nurturing healthy soil, wisely managing water, caring for pollinators—”

Yes. Yes we do. But above all we need to face the coming decades with a coherent vision that recognizes that just as there is no binary choice between ecology and economy, there is no binary choice between adapt and mitigate either.

We have to adapt and mitigate, until those two are the same thing. Well-designed solutions do both: if they reduce emissions and other impacts before we reach +2°c, they will be more efficient and sustainable in the times afterward. Likewise, if localized community systems will be better for living after the tipping point, they will probably also be good ingredients of a humane, holistic attempt to mitigate climate change to whatever degree is still possible.

The popular meme comes to mind — “ok, take for granted there IS no global warming. Isn’t it still a good idea to reduce diesel emissions in vulnerable communities, reduce acid rain, and preserve the Canadian forests destroyed by tar sands extraction?”

We can all agree that it is. And likewise, what is the downside of any climate-change mitigation measure if it’s done properly to begin with? If the alternative is business-as-usual oil extraction or mass-consumption and waste, it’s time to fund it.

The Future Today: Ethiopians Planted 353,633,660 Trees… in a Single Day

Room for restored forests in Ethiopia, and in Ethiopians a sense of limitless capacity.

Shouldn’t all the headlines look like that? The people of Ethiopia planted 353 million trees in 12 hours on July 29. The kind of story that makes you feel like there isn’t a problem in the world that can’t be solved… doesn’t it.

Forget, for a moment, the heartbreaking fires raging from Bolivia to Siberia, forget this month being on track to become the hottest July in recorded history — perhaps the hottest month in recorded history (update: true.). Instead, turn your eyes again toward a country whose peace deal with neighboring Eritrea is still fresh in the world’s mind (update: and still holding). Ethiopia is restoring its lost forests.

Ethiopia is no stranger to innovative projects that can help show a path toward sustainability. We’re watching progress in the highlands of Tigray and in Adisghe County, where earlier this decade, the government and farmers collaborated to cut through a historic drought to reverse desertification and save farmlands by slowing the flow of water to make better use of natural irrigation.

Today, mindful of the reduction of tree cover from 35 percent a hundred years ago to just four percent today, a reported 23 million Ethiopians mobilized to plant these trees, part of a much larger project that intends to plant four billion seedlings duiring this rainy season.

If confirmed, this collective effort would beat the previous record for a one-day tree planting; in 2017, 1.5 million Indian citizens planted 66 million trees. We’ll follow these projects in the future to see just how many seedlings planted in the excitement of record-breaking human endeavor are actual viable trees; how many of the thousand sites planted on July 29 become actual forests. But however effective the tree planting, we’d argue that the more important statistic is unprecedented public engagement: 23 million Ethiopians planting seeds of hope and effort toward restoring its country’s forests and the world’s climate.

Let’s follow that.

Sometimes soil just seems to want its forest back.

August update: The BBC’s “Reality Check” team has investigated this further and thinks, well, it’s possible they reached these numbers in Ethiopia. Their new article adds more interesting information about how this effort was organized, how more than 300 million seedlings might have been distributed and planted, on perhaps a million acres of land. It’ll be fertile territory for further study.

Meantime, a new study by Swiss University ETH Zurich reinforces the power of tree planting to mitigate climate change. As CNN reports, the study suggests that “restoring the world’s lost forests could remove two thirds of all the planet-warming carbon that is in the atmosphere because of human activity.”

We’ll come back to this later. In the meantime, plant trees.

Movie Night: “Fleeing Climate Change” (DW Documentary)

Up for a Friday-night movie?

Germany’s DW Documentary presents a concise half-feature on the “climate exodus” from the Sahel Zone in Central Africa, Indonesia, and the Russian Tundra: a primer on climate migration in case you need motivation.

End of the Drought: Central Valley Tree-velogue

According to yesterday’s monthly drought report from NOAA, all the rain and snow these last few years have finally done the trick. “As of March 12, the entire state of California was drought-free … for the first time in eight years,” the agency said, to a largely quiet public.

How are such announcements not met with ticker-tape parades? Isn’t this the end of a war? For our part, we didn’t mobilize a float to celebrate, but we did go take a look at California’s Central Valley, and it looked largely post-drought indeed. Setting out from Los Angeles we found late snow on the Grapevine and met rain in Bakersfield. We visited farms that are typically golden but now are green and lush; we stopped to gawk at overflowing rivers that cut through fields of yellow wildflowers and bright green grass you could almost hear growing.

Though the world looks verdant and fertile and neon and alive, it’s punctuated by dark trees that haven’t begun to sprout new leaves this spring. Many in fact will never sprout new leaves again. The drought is believed to have killed 100 million trees in California’s forests, and here, dead and stressed oaks, sycamores, willows, and other landscape trees lord over wide green vistas and line creeks and rivers swollen with snow melt and rainfall.

You get the same feeling down here as you do in the nearby Sierras, where sickly, drought-stricken oaks give way at higher elevations to sickly, drought-stricken alpine evergreens. The drought is over for now, but can the trees recover on their own? We may need a Marshall Plan for the trees. (This is a swollen Deer Creek, just north of Terra Bella.)

We drove the roads around Highway 65, which runs parallel to I-5 and I-99 into the hard-working farming communities of the Central Valley. You start to appreciate the sheer volume of agricultural endeavor not long after leaving Bakersfield.

According to a convenient USGS fact sheet, this valley contains 75% of California’s irrigated land and 17% of the nation’s. It produces 8% of U.S. agricultural output and a quarter of the nation’s food on just a single percent of the country’s farmland. Farmers here grow 40% of the fruits, nuts, and other “table foods” of the United States. It’s a haul worth $17 billion annually, made up of 250 crops in all, all made possible by water that needs to remain plentiful for the food to remain plentiful.

There are some ranches and occasional low-lying crops, but Highway 65 and its tributaries keep you focused on orchards — especially the mandarins better known to U.S. consumers as Halos or Cuties and the almonds that are right now in their spectacular pink blossom.

The immense popularity of the almond keeps water pumping, drought or not, supporting a thirsty crop that requires 1.1 gallons (or less) per nut. But the agricultural trees, too, bear the scars of drought. Abandoned orchards were more common this year than we have seen before, their black, craggy forms haunting the lush, green carpets of spring.

Strolling those retired groves feels like nothing more than visiting an old graveyard — eerily silent even in a stiff breeze as the branches dry in the sun and birds of prey circle overhead.

But as you drive north through the valley, the irrigated orchards rise in radiant health, covered as they are in their unreal pink blossoms of spring. What more appropriate monuments could there be to modern tastes and the extraordinary feats of engineering needed to maintain them, than these trees in their perfect lines, covered in pink for one blissful moment each year with a snow-white velvet carpet over their insatiable root systems?

The Central Valley grows approximately 80 percent of the world’s farmed almonds. This is both a triumph of the human spirit and also an assault on the earth which is draining the aquifers and stressing remote rivers which themselves bear other responsibilities to cities, more local farms, and entire ecosystems.

The industry has made strides to keep their crops healthy with less water — such as super-targeted micro-irrigation, which sends water underground, straight to the roots. They are experimenting with heavy mulching by, for instance, recycling entire orchards straight into the ground. Compared with burning and remote mulching, entire-orchard mulching can “sequester carbon at a higher rate, have higher levels of soil organic matter, increased soil fertility, increased water retention, and help reduce the global emission of greenhouse gases.”

Even more than the blossoms, the enduring image we’ll take away from this drive is the sight of dead orchards rising over bright green spring grass. It’s a joy to celebrate the end of an eight-year drought, but the question lingers in the air: are we going to keep depleting the water table and redirecting rivers to sustain crops that are not supposed to be on this land, even during normal rainfall?

If we’re indeed making a genuine effort to stop global warming and to begin adapting to what we can’t stop, can we expect California’s Central Valley and its hard-working farmers to supply a significant portion of the United States — and the world — with these beloved crops?

Both local and global climate changes are abruptly modifying not just the amount of water the land, the aquifers, and the rivers receive, but also the time of year they receive it. The science is heartbreaking, clear, and plentiful (wonks should see the 2018 study in Agronomy), demonstrating that while drought presents itself cyclically, within no more than 30-50 years the Central Valley will no longer be able to support the same kind of agriculture it now hosts with such grace and plenty.

So the traveler can take comfort in a battle won, but not the end of a war from which we can expect to start rebuilding — and re-seedling-ing.

Trees rising lifeless from this land seem to be calling for a plan to restore their lost numbers. But what we need is much, much bigger thinking, and more strategic and smart investment, to ensure that the ecology can sustain whatever lives here — for our sake, but also for the larger sake of the ecology as a whole, including the trees that were here long before we arrived with our technology and our expensive tastes.

•

We eventually re-joined route 99 and ended up in the empire of almonds outside Davis, but not before having the experience of watching all that agriculture fly by, mile after mile, with its suggestion that any human endeavor we set our minds to is possible in any volume we need to maintain life.

Lessons on Resilience from the Oaks

Looking back at the “fire season” which only now seems to have “ended,” I’m remembering a trip I took out to Las Virgenes deep in the San Fernando Valley near Calabasas late last year, while the Woolsey Fire was still raging in all directions. Looking around, the oaks were the obvious subject of the story of burned hillsides.

As I wrote a journalist friend at the time, on many hillsides:

“the oaks sit alone in a newly desolate landscape. Their survival seems unlikely, but what few humans — even local ones — seem to know is that if healthy, the California live oak is resilient to fire; in fact it thrives in a landscape cleared periodically this way. So they stand still, alive, moist, in fields of ash, seeming to know exactly what they are doing… the trees have held their own.”

Construction had resumed in a new development on the site of a former ranch in Liberty Canyon, even as fires burned on adjacent hillsides and fire units patrolled within sight for flare-ups. The flames had burned right up to to the new buildings, where their lawns by now have probably already been rolled.

I met a rancher who had been able to evacuate his horses very early, and had lost no livestock and just one small building. He asked that I not photograph that building — “it’s all traumatic enough already.” His land was now dominated by the oaks, and we admired them together for a while. He said they had lost more trees than usual this time, though. “Fires come and go,” he said, but the drought has been persistent, and the drought-stressed groves were gone.

The University of California Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources hosts UC Oaks, a comprehensive resource on California’s oaks, including numerous planning and policy projects designed in particular to reduce the pressure of development on the oaks’ numbers.

But these trees live hundreds of years, and the reality is if we’re going to learn lessons from oaks as well as for them, we had better take things a step further than preserving existing oaks — and get planting.

“The Forensics Have Spoken, and We Are to Blame.”

Terminal Dock, San de Fuca, Washington.

We spent much of August at Penn Cove, on Whidbey Island, Washington. This will be remembered as the year a blanket of smoke moved in on August 14 and did not leave. The sun turned into an orange moonish ball, the horizons disappeared.

On August 24, as fires still burned in California, Oregon, Idaho, Washington, and British Columbia, Gavin Schmidt, the director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, wrote an opinion article in the New York Times: “How Scientists Cracked the Climate Change Case.” By all accounts such an article is not something that should have been necessary at this point to write. And, if it were necessary, such an article should have been the period on the sentence on the who and the what, vis-à-vis blame for climate change.

Kayaking on Penn Cove, with destination mussel rafts visible but no horizon.

Setting the scene:

“For the past 100 years we have documented good, independently confirmed observations of change at the surface of the planet, and for the past 40 years satellites and comprehensive measuring efforts have provided a much fuller view of changes throughout the earth system. These observations show clearly that among other things, the surface of the planet has warmed, the upper atmosphere has cooled, the oceans are gaining an enormous amount of heat, sea level is rising, Arctic ice has greatly receded and glaciers around the world are in retreat.”

These are observable, demonstrable facts, facts about data, facts seemingly immune to the powerful psychological embrace of denial, facts uncontroversial by now even among some tea-party Americans and others among the world’s conspiracists who long believed that mainstream science was hiding something behind its climate assertions, and yes also that Elvis is still alive, that men never landed on the moon, and that contrails contain chemicals to control our thinking about all these subjects and many more.

While some of those people may have begun to admit the existence of climate change, the question of who or what deserves the blame for it remains to them up in the air. This question is just as important to them — because after all, if humans are not responsible, then there is no reason to change our behavior or adapt our lives to face the consequences of not doing so.

Schmidt continues straightaway: “Scientists have no shortage of suspects for the causes of climate change,” and pays respect to volcanoes, asteroids, and the flutterings of the sun — bugaboos that conspiracists point to in their desperation to continue blamelessly driving cars with deplorable gas mileage, air-conditioning all the empty rooms in their houses, and converting raw materials into landfill with wild abandon.

Then three tight paragraphs explain away any cause that isn’t humanity’s misbehavior, and Schmidt concludes that:

“Even more convincingly, these trends aren’t just being attributed in hindsight. The rate of surface warming was predicted in the 1980s, the cooling in the upper atmosphere was forecast in a 1967 scientific paper, and specific measurements from space indicate that the total greenhouse effect has been enhanced exactly as theory would predict.”

We all know, or else we try not to know, that “Our best assessment is therefore that humans, at least the ones responsible for the bulk of carbon dioxide emissions, have been responsible for all of the recent trends in global temperatures. The forensics have spoken, and we are to blame.”

In this context, we floated on the waters of Penn Cove — themselves warming like the air, and rising due to glacial melt, and acidifying — and wondered how much of what we think is essential is actually behavior that we need. How much of adapting to climate change will be simply doing less of what we don’t need to do or care about doing?

Early sunrise, reduced to its most basic elements by airborne particulate matter.

Adaptation: It’s a Mouthful

ADAPTATION.

A bad word, a stigma. Still, we ought to try it out. Adaptation. Give it a chance. Adaptation. Pull it on, one limb at a time, four limbs, like new coveralls. A-dap-ta-tion.

Time to roll it back and forth on our tongue, see how it sounds in the titles of poems, movies, novels, songs, blogs. The Road Less Adapted. The Grapes of Adaptation. Adaptation On My Mind. For Whom the Bell Adapts. Citizen Adaptation. Kramer vs. Adaptation. (Doesn’t always work.)

It’s a bad word, profane, vile, heretical. Prevention is much better. Everybody loves prevention. Prevention sez it’s not too late to reverse climate change. Prevention says it’s not too late to make things like they were. Prevention means the system dwarfs the damage we’ve done to it. Prevention means we can live like modern humans live and still find harmony with our environment. Prevention means we can keep growing our cities and economies and houses and businesses and portfolios and still purchase and consume, still build and make things with the supreme virtuous objective humans have always lived for above all things: to provide for our families a wee bit better than our parents did.

Prevention means we can still spit in the river, still tilt into the wind, still casually spend our Sundays at the park just like we always have.

Better times? George Seurat, “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte” 1884-1886. Art Institute of Chicago.

Prevention of climate change means keeping everything we know. Prevention means looking forward to a recognizable wedding twenty years from now. Prevention means starting a business today in order to pass it to our children. Prevention means we can plant an acorn next to our house to shade our great-great grandchildren in the yard. Prevention is comfort.

But adaptation…

The water is rising. The dike is cracked; it’s leaking. We have a finger in it. Adaptation may sound like giving up — pulling our finger out, hopping into the best rowboat we can find, and waiting to ride the surf. But the dam is cracked and taking on water, and bits are falling off.

Adaptation doesn’t mean we won’t prevent climate changes that we still can prevent, but folks hello: it’s time to adapt.

And look: this sunset is very, very beautiful.

Yellowcaps?

On Saturday I called them “disturbing, unpretty yellowcaps.”

I get why they are disturbing. Our eyes are accustomed to seeing a gentle blueish white in the highlights off the top of the sea. The yellow color is wrong.

But is it “unpretty”?

If we adapt, will our eyes eventually adjust? Will our children’s children’s midwestern inlaws come to the coast in November for the glittering yellowcap season?

Hmm.

Sand and Ash

This is one of those days of public emergency where nothing’s really stopping you from taking a walk on the beach. Nothing logistical, anyway, as long as you don’t want to drive to Malibu. And as long as you don’t mind breathing air heavy with smoke and ash, and as long as you don’t object to sheet-white skies with oyster-shell highlights, and aren’t turned off by reflections in the water roughly the color of butter, and disturbing, unpretty yellowcaps spotting the surf.

Sometimes when there’s a forest fire nearby, you get an entire day of golden twilight color, and spectacular sunsets thanks to infinite reflections of sunlight off airborne particulate matter. This is not one of those days. The air contains way too many dead oak trees and scrub bushes to allow beautiful light to glimmer between clouds of smoke. Don’t look for a silver lining of any kind because there isn’t one.

A mid-November day like this would usually see cars lined up all along Pacific Coast Highway, parked bumper to bumper on the beach side and stopping-and-going in the traffic lanes. Families would be pulling out their coolers and strollers and blankets, dragging them all along the path down to the shore, and staking their claim on the soft sand to spend the day in the surf. It’s the kind of November day that’s usually broadcast to friends and families back home in northern places: hey, look where we are in November! Look what we’re doing in November! How are you enjoying the rain? Is it snowing yet? Haha!

Today the beach flags are flying at half mast, and PCH is empty from where I-10 meets the coast to the spot several miles to the north where a police barricade stops you at Sunset Boulevard. At that point you can park your car wherever and hike north — if you want.

The only people here are the ironic types, and fishermen, and some unsmiling tourists. I park near Gladstone’s restaurant and walk up the beach with my camera. It’s all the same buildings as usual. The same crashing waves. The same number of steps to the shore, roughly.

They say the late summer and autumn will blend into an annual “fire season.” If they do, will people someday flock here to experience this quiet dystopia? Will they take advantage of the beach in their usual droves, fleeing the less profound settings in their urban apartments and Valley subdivisions? Will they sip cocktails on Gladstones’ porch to watch the waves crashing in the smoky air, or let their kids kick the water and chase the hardy birds?

The sun is a circle of white and ash drifts in the dimples in the sand. As I walk back to my car I realize it is an extra effort to breathe. I’ll pay for this later.

All reports suggest that further climate change is coming, regardless of what we do now. We have to adjust. Can we adjust to this?

A guy walks toward me wearing a backpack and a face mask, holding a crowbar or some other authoritative thing. He seems resolute, like someone who came to this beach, today, intentionally, maybe because of all of the above.

Today it looks like he’s got some answers.

The Ivanpah Solar Power Facility Is Home in the Mojave

Ivanpah Solar Power Facility sits in a dry lake bed in the Mojave Desert, just west of the Nevada border. Here the foreground is the old dry lake bed; the background is Clark Mountain.

The Ivanpah Solar Power Facility is shocking. If you’re heading from Los Angeles to Las Vegas on I-15, the new sustainable energy plant might give you whiplash as you complete your descent of the graceful desert mountain pass that cuts between Clark Mountain and Kokoweef Peak.

The pass is no more than five miles long in both ascent and descent, but its erosion patterns, loose stones, rough scrub, and playful dance of sky and hill make for satisfying desert drama as you drive east. In the days before modern engines, the little pass was enough to overheat radiators finally exhausted by the long Mojave miles. As energy-related surprises go, Ivanpah is far more welcome: as the last stretch of descent gracefully bends toward the left, the plant’s three boilers and thousands of mirrors peek through the hills and then spread out in the distance: three inexplicable circular mirages of inexplicable white light on an otherwise uniform brown desert floor.

Ivanpah came online in 2014, and it was all-new. It employs no photo-voltaic cells in its daily generation of a max 440 kilowatts of electricity. It’s a solar thermal plant with three circular arrays of thousands of software-controlled, sun-tracking mirrors that direct light and heat into the three 450-foot-tall water-filled boilers. Those boilers heat the water to 550 degrees fahrenheit and create high-temperature steam that turns turbines and generates electricity. Even though it burns a certain amount of natural gas every morning to get the whole system running, it is a smokestack-free source of power for California’s Bay Area, and relatively self-maintaining compared to traditional power plants.

We want to love it. We want it to exist in a promise of harmony with the graceful hillsides, with the sunset colors of evening, with the desert tortoise it displaced from its footprint, with all the mystery of the desert we know in our hearts we’re supposed to leave-the-f%$-alone. But there’s no denying that from a conversationist’s perspective, Ivanpah is a shocking and incongruous thing to sit in a formerly pristine dry lake bed.

Nevertheless, in its stark, extreme, lonesome incongruity it does feel at home in the Mojave. The desert is inexplicable itself, and so it is kind to inexplicable things. It seems to love its ruins of impossible buildings, the crumbling billboards advertising incongruous anachronisms, the artifacts of improbable crops or businesses long expired, all those fading testimonies to human dreams that found harmony of some kind with the desert.

The desert’s lonely judgment is not as kind to the nearby casino oasis of Primm, a kitsch attraction that lies a few miles to the east across the Nevada border. Primm is a freewayside collection of theme hotels, parking garages shaped like storybook castles, and brand-splattered factory outlets, placed where it is for obvious (and highly explicable) reasons. The very existence of Primm is itself a strong enough parry against any environmental and aesthetic objections to a clean power plant nearby.

The solar plant complicates the view of Clark Mountain and its neighbors, seen here from a Primm casino rooftop in Nevada. (All images by the author, 2018, except George O’Keefe.)

After all, are we to hold up our clean power plants to a higher standard than everything else we build, including the latest air-conditioned playground for people looking for new ways to part with a few bucks without having to drive the extra 43 miles to Las Vegas?

“People Don’t Realize Deserts Are Important”

Well, yes. Our efforts at improving ourselves do need to avoid environmental hypocrisy. And while Ivanpah’s construction created surprisingly little drama of the Chinatown sort, it has been subject to environmental scrutiny.

As with windmills, the most significant burden of this solar thermal plant seems to be borne by birds. It’s a nightmarish scenario: bugs are drawn to the extraordinary brightness of the sun-mirroring heliostats; those bugs attract birds and bats, which attract larger birds. Some birds are immolated on the sharp features of the mirrors as they chase bugs through the lights. Others, burned by intense radiation between the heliostats and the boilers, are known as “streakers” as they fall to the ground. The numbers of avian victims range from hundreds to tens of thousands annually, and include the Mourning Dove, the pink-throated Anna’s Hummingbird, and the Greater Roadrunner, as chronicled in a fascinating article at the Pulitzer Center, “The Fall of Icaraus: Ivanpah’s Solar Controversy.”

The relationship betwen human beings and the desert is as fascinating as it has been frought with peril. Human attitudes range from Georgia O’Keefe’s loving obsession with the desert landscape, to the hostility we ourselves used to witness in developers and brokers who were part of Las Vegas’ extraordinary expansion in the first decade of this century: evangelists in their desire to tame the unknown and bring it into the comfortable human realm and under human dominion.

Georgia O’Keeffe with Painting in the Desert, N.M., 1960. Tony Vaccaro (American, b. 1922). Chromogenic print; 35.2 x 45.7 cm (13 7/8 x 18 in.). Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, 2007.3.2. Photo: Tony Vaccaro/Tony Vaccaro Studio. Borrowed from this Cleveland Museum of Art article in Medium about Georgia O’Keefe — we’re as obsessed with her as she was with the American desert.

In between these poles are the rest of humanity and a blend of fear and apathy. The desert does not enjoy the uncritical adoration humans lavish on oceans and forests.

As Janine Blaeloch of the Western Lands Project notes in the Pulitzer Center article, “People don’t realize deserts are important.” But the dry lake bed in the desert is nevertheless a gorgeous habitat of both flora and fauna in the Mojave Desert:

Many of the species found in the Mojave are endemic to the region, meaning all members of that species are entirely located within that specific area. Contrary to the typical perception of deserts as barren areas, they are, in fact, biologically rich. Many endangered or threatened species live in these fragile desert ecosystems, including the Yuma Clapper Rail. One threatened species, the desert tortoise, received most of the attention before and during construction of Ivanpah. When construction began, workers expected to find 30 tortoises on site. There were actually over 170. These tortoises were successfully relocated, as part of the largest private study on desert tortoises ever done, and the three companies funded hatching, rearing, and releasing of over 50 tortoises in a dedicated nursery on site. Additionally, special-status plants were transplanted to a designated area also at Ivanpah.

This century will be the story of the deepening of our relationship with every single thing around us — a recognition of how we impact our surroundings and vice-versa. This will be a welcome return to a primary, lost component of our species’ very consciousness, but it will also complicate how we rebuild our part of the world so that we can sustain our presence here.

If we know that a solar thermal plant incinerates birds, can we still build it? What if we know an equal number of birds aren’t killed running into equivalent coal smokestacks, or by the acid rain of our coal energy infrastructure?

“Anytime we [do] something new, there’ll be bugs,” explains Doug Davis, compliance officer at NRG, which runs the plant, in the Pulitzer Center article. “There’s a learning curve to this.”

It’s a steep learning curve, but there’s no reason to think it can’t be as graceful as a desert mountain pass where we’re as focused on a long horizon and a safe arrival as anybody keeping their car between the lines on the Mojave Freeway.

Perhaps we are as inexplicable to the desert as the desert is to us.

Leave the Plunger Alone, and Let Your Clover Grow

In the classic Looney Tunes gag, Wile E. Coyote has bought his classic ACME detonator and deployed some TNT to do the Road Runner in. As the bird approaches, the coyote hits the plunger. The plunger jams in typical form, and the harder the Coyote fights it, the stronger it resists. He jumps on it, smashes it into the ground, strains as much as possible. But as soon as he abandons it to its own will, it gently detonates on its own — just as the canine himself reaches the target.

The gag works, of course, because we all know how unproductive, and sometimes even counter-productive, a bad plan can be. We are all Wile E. Coyote at his own undoing.

In the case of climate change, even some of the best plans seem prohibitively, impossibly, difficult. Moving forward, we believe that some of the best ideas to address climate change are yet to be thought up, and many of those that make the biggest difference will be the simplest of all. It can’t all be done by plucking the “low-hanging fruit,” but the most impact will be had by good ideas that recognize points of resistance and predict opportunities for mass-uptake and for scale.

Addressing the parallel crisis of the terrifying and ominous decline of honeybees, the well-named Michelle Wisdom, a researcher at the University of Arkansas, helped point to an area where we can potentially help by doing little work. In fact, she may have found a way to leverage the opposite of work — hordes of weekend warriors staying on the couch and leaving their lawnmowers in the garage — to help bees.

An Arkansas grad student and hobbyist beekeeper, Wisdom joined a research project exploring the impact of introducing plants that can sustain and feed honeybees and other pollinators. much of whose decline can be attributed to habitat loss.

As the University of Arkansas reports, “according to USDA sources, more than 50 million acres of manicured lawns, golf courses, roadsides and other managed turfgrass surfaces make grass the largest agricultural crop in the U.S. Add Monoculture farmlands and the result is that pollinator habitats have become fragmented.”

We are willing to speculate that 50 million acres of land would go a long way toward re-de-fragmenting habitats of honeybees and other pollinators.

The research project emphasized the planting of bulbs. Even after beginning to create efficient ways to do that, Wisdom couldn’t see much change in bee behavior and began to look for other sources of nutrients. The university continues,

“Wisdom … wanted to see if she could find flowering plants that could coexist with bermudagrass or buffalograss during the insects’ active season. She said her goal was to create a succession of blooms from early spring through late fall. ‘A succession of blooms is best for pollinators,’ she said. ‘Most require diverse pollen sources for good health. And they also need a season-long succession of food sources.’” The trick with the later flowers was finding plants that not only could coexist with the grasses, but also survive repeated mowings. She was able to find a combination of bulbs, white clovers and a couple other flowering plants that provided a succession of blooms. In addition to contributing to pollinator habitat, the white clovers are legumes that make their own nitrogen and leave enough of it in the soil to help fertilize the grass. The combination provided a succession of blooms from as early as January through as late as November.”

This article doesn’t conclude that white clover is adequate in and of itself to sustain the kind of bee habitat we now need. But while the massive planting of bulbs may not be feasible without a national campaign of the sort we may need for, for example, planting trees, making white clover available to bees can be as simple as not mowing the lawn, or as not rooting out the soft, lush, and often very pretty plants in the service of a monocultural lawn.

Plus, while you’re busy not preventing your clover from blossoming, you’ll also leave some of your lawnmower’s carbon diet under the ground where it is much better off. And sure, not mowing the lawn won’t help the climate on a scale of fifty million anythings, but every effort — or lack of effort where appropriate — counts.

In addition to providing food and habitat for honeybees, white clover is arguably prettier than grass and no more thirsty. It isn’t trample-proof on its own, but combined with lawn it is a resilient and soft habitat for human beings as well.

All imagery by the author, except “Gee Whiz-z-z-z-z-z-z,” 1965, Warner Bros. Pictures Inc., directed by the incomparable Chuck M. Jones.

What If Electric Car Journalism Succeeded?

Just like most early electric cars, media coverage of the EV industry just looks, er… different.

The cover article in this week’s Newsweek is a case in point. “What If Elon Musk Succeeds? Tesla, SpaceX Founder Wants to Transform Technology—and Put Humans out of Work.” The writer, the usually thoughtful David H. Freedman, opens the article with eight paragraphs focusing on the manic tweeting and general eccentricity of Tesla’s CEO, Elon Musk — only to then turn around and say, “But if you’re focusing on Musk’s ‘bad manners,’ as he called his meltdown, you’re missing the point.”

Leaving aside the weirdly transparent exercise in projection, it’s what comes next that’s so strange:

His plan to transform the car industry is picking up speed. Along the way, it could put tens of millions of people out of work (and that’s not a bug, it’s a feature), dismantling what has been a foundation of the nation’s social and economic life for a century. And it’s happening in the service of plying the wealthy with cooler cars. “Technological innovation has throughout history increased total wealth,” says Ryan Lackey, a founder of cybersecurity company ResetSecurity and a veteran Silicon Valley entrepreneur. “But it’s often said the gains are going to a smaller and smaller subset of the population.” So the worrisome future may be one not where Musk fails but where he succeeds.

Is there any other industry where advancements in automation are spun as a diabolical plot by an evil mastermind hell-bent on destroying the working class?

Of course, ALL automation puts people out of work, but didn’t we long ago accept this, if only sometimes begrudgingly, as an inevitable byproduct of the passage of time?

Is a printing machine that no longer requires a full-time maintenance staff so diabolical? Are larger combines or wider plows demons deployed by the agriculture industry “in the service of plying the wealthy,” who are always first in line for enhanced products of any kind? Doesn’t the newly inexpensive print-on-demand industry borne of better printers first benefit the rich, who are still buying new hardbacks, before it benefits everyone else?

And what of the rest of the auto industry’s century-long effort to replace workers with machines? Is it only OK if it’s in the service of propping up obsolete drive trains fueled by petroleum? Is it only OK if it puts midwesterners out of work, as opposed to Californians?

And isn’t this an industry that has been increasingly happy to move entire manufacturing processes to other states, or other countries?

(And why not, as long as I’m playing “other people do it, too” cards, we might as well imagine the horror movie of Henry Ford with a Twitter account. Venerable Ford Motor Co., if there’s justice in the world, might never have survived to become an engine of the economy now so threatened by Musk’s efforts to streamline manufacturing.)

Tesla’s diabolical plan was to do for electric cars what China is doing for solar technology — but instead of in an autocracy, doing it within a capitalist system; and instead of using government fiat, using irresistable industrial design.

The fetishizing of 21st-century celebrity CEOs is a distraction. The actual truth is that no matter how powerful Elon Musk becomes, he’s not the one who gets to decide what happens to workers after a machine replaces their jobs.

Because while a human worker may or may not be needed in the process of turning raw steel into a sensuously curved door panel, but there can never be too many childcare workers.

Imagine a factory line with nine workers, and an adjoining childcare center with one carer for all 10 workers’ pre-school children. If automation eliminates five factory jobs, society could choose to have six carers for the 10 workers’ children — and still, nobody out of work.

Likewise, there can never be too many healthcare workers. There can never be too many social workers. There can never be too many geriatric workers. There can never be too many firefighters, never too many people cleaning plastic out of the rivers, lakes, and oceans. Never too many people cleaning superfund sites, never too many people preventing new superfund sites.

Whether automation is a bug or a feature is not Elon Musk’s choice — it is all of ours.

By now it’s pretty clear that Elon Musk has already succeeded. His purpose with Tesla was clear from the beginning: creating an existentially important viable technology (electric cars), and public demand for it, where they simply did not exist before. He is still following his blueprint — 1. fancy roadster for fanatics; 2. fancy sedan for the wealthy, 3. progressively cheaper cars for everyone else — and while there have been bumps in the road for Tesla investors, very few are jumping out how.

But if anything, in his stated larger purpose of transforming the auto industry, he has been able to step on the accelerator, certainly hastening the demise of internal combustion by open-sourcing Tesla’s patents and inspiring massive fleets of new EVs on the drawing boards of nearly every one of his competitors.

Yet Newsweek’s question remains, “What If Elon Musk Succeeds?”.

I ask, in response, what if Newsweek “succeeded” in publishing this same article about an offshore wind (or even natural gas) CEO vs. coal mining, even when the only people arguing for old coal now are politicians pandering for the coal-miner votes?

Would they condemn natural gas though it is a cleaner, more efficient energy that employs fewer people per unit of energy, on the strength of eight paragraphs of weird tweets?

Don’t get me wrong. Journalists have done extraordinary work covering climate change, alternate energy, and even electric cars. But this is a vote for perspective as humanity turns to ever more oddballs willing to disrupt ever more industries and fix our mess.

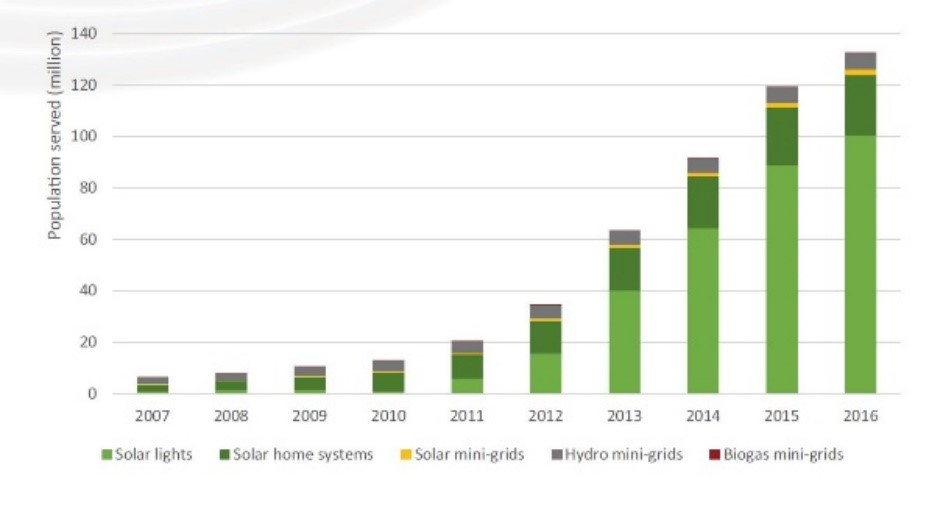

Mobile Phones Leapfrogged Landlines. Will Off-grid Renewable Energy Do the Same to Coal Plants & Power Lines?

In the first years of this century, when inexpensive cell phones spread low-cost, ubiquitous communications around the world, another amazing thing happened: the rationale for wiring the developing world for telephones vanished. Cellular technology rapidly leapfrogged old-timey telecom’s slow-motion efforts to wire remote outposts (in Africa, for instance: 2004, 2009, Pew 2015), providing phone, and later Internet, banking, and other services where they had never existed before. No matter what you think of resulting social changes, nobody mourned the utility poles, wire, labor, and time not spent on a telephone grid.

A similar revolution in energy has even more potential to reduce wasteful infrastructure and emissions, and establish a solid basis for sustainable energy around the world. “Off-Grid Rewable Energy Solutions” (download), a report released last month by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), demonstrates considerable momentum in the movement to generate power locally, outside the legacy webs of wires connecting everyone to centralized, fossil-burning power plants.

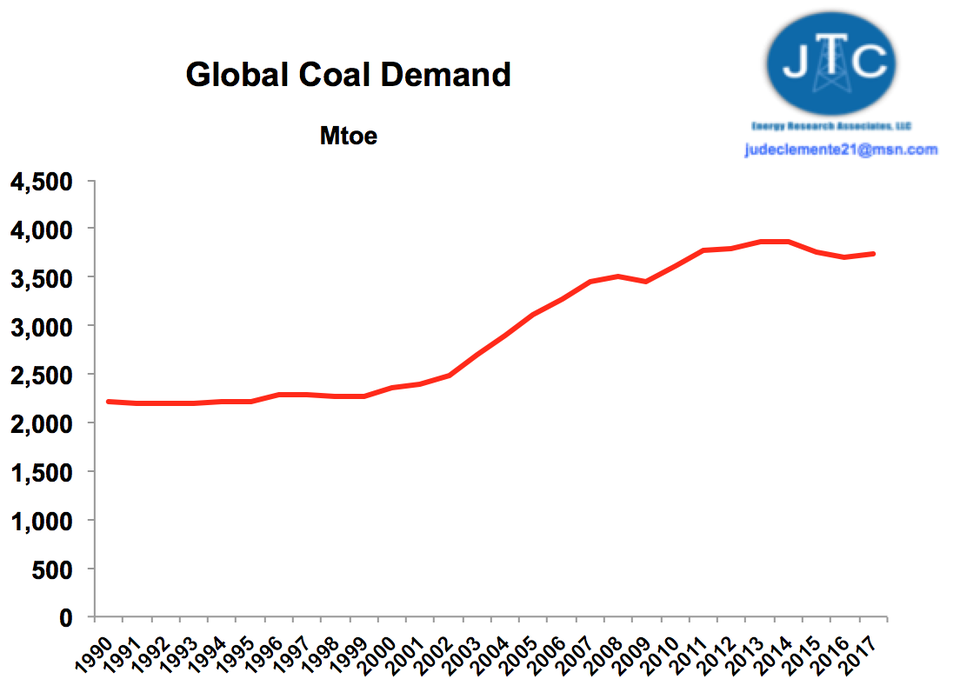

This development doesn’t arrive a minute too soon — unbelievably, the global market for coal continued to grow last year even as the consequences of burning fossil fuels have become more and more clear.

(Thanks to Forbes for a graph that looks like it’s got the century wrong.)

Ready to Scale

Of course, decentralized power is nothing new. Windmills have been used to pump water and move cogs for 1,500 years. The water wheel is still hundreds of years older. In recent decades, small-scale solar has joined these old technologies to begin delivering electricity far from any grids, creating new communications possibilities and also aiming to replace the burning of wood, coal, and other materials for cooking and home heating, and reduce burdens of these on respiratory health.

Solar has sometimes been better in theory than in practice. This glass-encased array was provided by a Dutch NGO to an orphanage in the outskirts of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Intended to power the bare light bulbs hanging above living spaces, the solar array soon stopped working and its treacherous shards of glass became useful only for drying laundry in the sun. Today, however, photovoltaic cells are remarkable for their lack of moving or breakable parts, promising zero maintenance cost over time — a big part of why solar energy may soon overtake all other energy sources for cost-effectiveness on all scales. (2006)

As solar technology has improved, we’ve begun to see hints of scalability, including market-based solutions like the delivery of lanterns that combined solar cells with super-efficient LED lights in order to reduce reliance on kerosene, candles, and other expensive and dangerous lighting fuels in countries such as Malawi.

Today, energy storage remains tricky, but the cost of a kilowatt of solar continues to drop at a rate of 12% year-over-year, meaning that every year, shoveling coal into furnaces to push power into wires is as crazy as it sounds.

Aside from being cleaner and more efficient, decentralizing power may have other important positive side effects in less stable areas, improving energy security by removing grids and large plants from the target lists of terrorists or warring nations

The development of off-grid power has the possibility not just to energize remote places — but to begin electrification without the inefficiencies of remote power delivery and establishing systems based permanently on renewable energy sources.

Case Studies

According to the above IRENA report, Asia leads the world in off-grid and small-grid power deployments. The organization highlights six different case studies in a separate report, all of them speaking to the power of not waiting for a wire to come from a dinosaur-burning power plant — but instead, generating the power cleanly and locally… and building from there.

in 2004, 1001fontaines installed 164 solar kiosks to bring fresh, clean water to remote villages in Cambodia — pumping and filtering groundwater and river water with additional UV purification. With 2018 technology, projects can provide critical services but also establish a foothold for infrastructure based on renewable energy.

If You Can Afford a Car, You Can Afford This EV

The Mitigaptationist is no “influencer,” but we’re not above pitching a product. In fact, we now present a full-throated endorsement of our own car, the second-generation Chevy Volt. We’ll do it here on economic grounds, and leave green-ness, technical quality, safety, joy to drive, and other virtues to better qualified reviewers (first-gen 2011 “Car of the Year,” second-gen 2016). To us, if you have to drive a car in the year 2018, while also caring about the impact of doing so, the Chevy Volt is the car to drive.

A lease is the best way to cash in on this cost-effective chance to help shift the American landscape from its hundreds of millions of automotive smokestacks to an altogether new energy paradigm. Nissan, Chevy, and BMW, to push their unconventional Leaf, Volt, and i3 into out into the world, have relied upon low-profit low-cost leases made cheaper by spreading out the $7,500 federal incentive over 36 months.

The cars are all technological wonders, but Chevy’s Volt is a bit confusing in that it has a 60-mile electric range (or 43 miles for the first generation) backed up by a generator. When the electric miles are fully spent, the generator silently kicks in and efficiently pushes the car’s torquey and playful electric drive for as long as you want it to. (For us, that meant that for as long as several months when we lived in an apartment building without EV chargers, we simply had a normal, quick, efficient, well-built internal combustion car, except when we could find a charger somewhere. Otherwise we almost never drive on gas. It’s literally two cars in one.)

Teslas argue themselves beautifully as the perfect car in a perfect scenario where transportaion budgets are limitless and charging is easy and plentful. But to us, the Volt is the perfect car for anyone who has a budget and any kind of need to be out of range of charging stations.

Sadly though, Chevy has never done a good job of marketing its tech wonder for just how cost-effective, and otherwise practical, it actually is. Say it: “we’ve made this cheap to own!” Say it: “there’s no range anxiety!”

The Volt (including the first-generation shown here) is really the perfect car for our collective transition from petroleum infrastructure to electric. Sadly, Chevy hasn’t made much of an effort to explain that to an audience that generally loves and embraces technological improvements. This ad was one of the better attempts.

Anyway, here are the numbers.

We took both our 2013 and 2016 Chevy Volts with typical leases that, at $229 a month, cost about the same as the monthly fuel bill of our previous 1996 Mercedes 320E (three tanks/month) and 2004 Saab 9-5 (four tanks/month). The down payments of around $3,000 were nearly offset by the state of California’s $2,500 tax rebates. Licensing and insurance for the new cars cost more than they did on the old dinosaur-drinkers, but maintenance on the two three-year leases was limited to rotating the tires and alignment on one of the two of them. Our electricity bill went up by an average of about $20/month, which we consider a nice trade-off for losing the guilt associated with internal combustion. (If you drive on electricity for a while and return to a V-8, you feel that guilt in your foot when you step on the accelerator.)

As you can see, those numbers are loose and they vary for every person depending on local energy cost, availability of government incentives, etc. But for us, driving brand-new Volts cost just about the same as the aging sedans they replaced — and that doesn’t begin to take into account the wider benefits of zero emissions, zero petroleum, and the critical mass created in the market by choosing a cleaner technology over the one that’s driving us into the ground.

Nor does that take into account the collective benefit of having a Chevy Volt on the road for, say, a lifetime of 15 years, rather than buying a new internal-combustion car and bringing into the world another being that’s going to need the petroleum infrastructure until the year 2032.

Will such an infrastructure even be feasible by then? And if feasible, will it be ethical? Questions better left for another time.

Cross-posted at the ClimateFightr Tumblr.